We need the tonic of wildness (…); to smell the whispering sedge where only some wilder and more solitary fowl builds her nest (…) We need to witness our own limits transgressed, and some life pasturing freely where we never wander.1

s'il n'y avait rien à savoir?2

In the synopsis of Epoch 1 – Prologue, the starting point of The Feral project, we are transported to the year 1023, more precisely to the epicenter of an event that occurred in Limousin (Limoges, France) that same year. A community of men and women heads towards the forest to indulge in a frenzied dance, plagued by hallucinations caused by rye spur3, where human bodies, plants, animals, and objects intertwine in an endless movement. This collective delirium, which historically recognizes factuality in the so-called "dancing epidemics"—outbreaks of behavior in which entire groups danced uninterruptedly, often to the point of exhaustion or death—embodies the founding scene that inaugurates The Feral's Artificial Intelligence (AI) programming. The symbolic choice of this event as the Prologue determines that the opening moment of the project is marked by the collapse of the rational and natural order—agricultural, ecclesiastical, and temporal: the seasons cease to obey, religion declares a Truce of God, rye putrefies. Before us we have the proposal of a cosmogony formulated in the moment of delirium of bodies in trance, and whose movements escape any codification, in the symbolic exodus to the forest, and in the sacrificial gesture of inoculation of the substance that, having been subsequently synthesized, finds its counterpart today in LSD. We find ourselves, then, before an event that represents the dissolution of the boundaries between body, mind, and Nature, that suspends the distinction between voluntary action and automatism, and that returns to gesture its non-finality. In the dilution of the subject, in the exaltation of the collective body, in the uncontrolled movement, gesture is assumed as prior to language, as opposed to representation.

This is the scenario that The Feral recreates with the aim of capturing, through dancers with 360° cameras, the first learning material of an artificial intelligence that is finally beginning its programming: an event that proposes to initiate a system through what we might call a "state of nonknowledge," evoking a kind of Bataillean consciousness.4 Note that, for Georges Bataille (1987-1962), nonknowledge is a state of latent force that involves one who do not serve, who is not useful, who lives outside the logics of production and submission. In this sense, it determines within itself an experience of freedom, contrary to what one might imagine, the freedom to spend, to waste, to die, and it is this act of radical nonknowledge that is constituted as a form of rebellion: to discontinue the obligation to produce meaning, to abandon utility, to refuse subjection to hegemonic discourse. The experience of nonknowledge is lived bodily: the subject unravels to touch excess, and it is precisely this uprooting that has the potential to found a form of non-utilitarian sovereignty, because it is not based on rights or titles, but on the capacity to invest in one's own limit in a radical way—death, sacrifice, ecstasy.5 The Feral, therefore, chooses to begin its AI's learning with a scene of collapse, the hallucinated dance thrown into excess and noise, a movement that, in its essence, recognizes the gesture of Bataillian nonknowledge. But, after all, what are we really talking about?

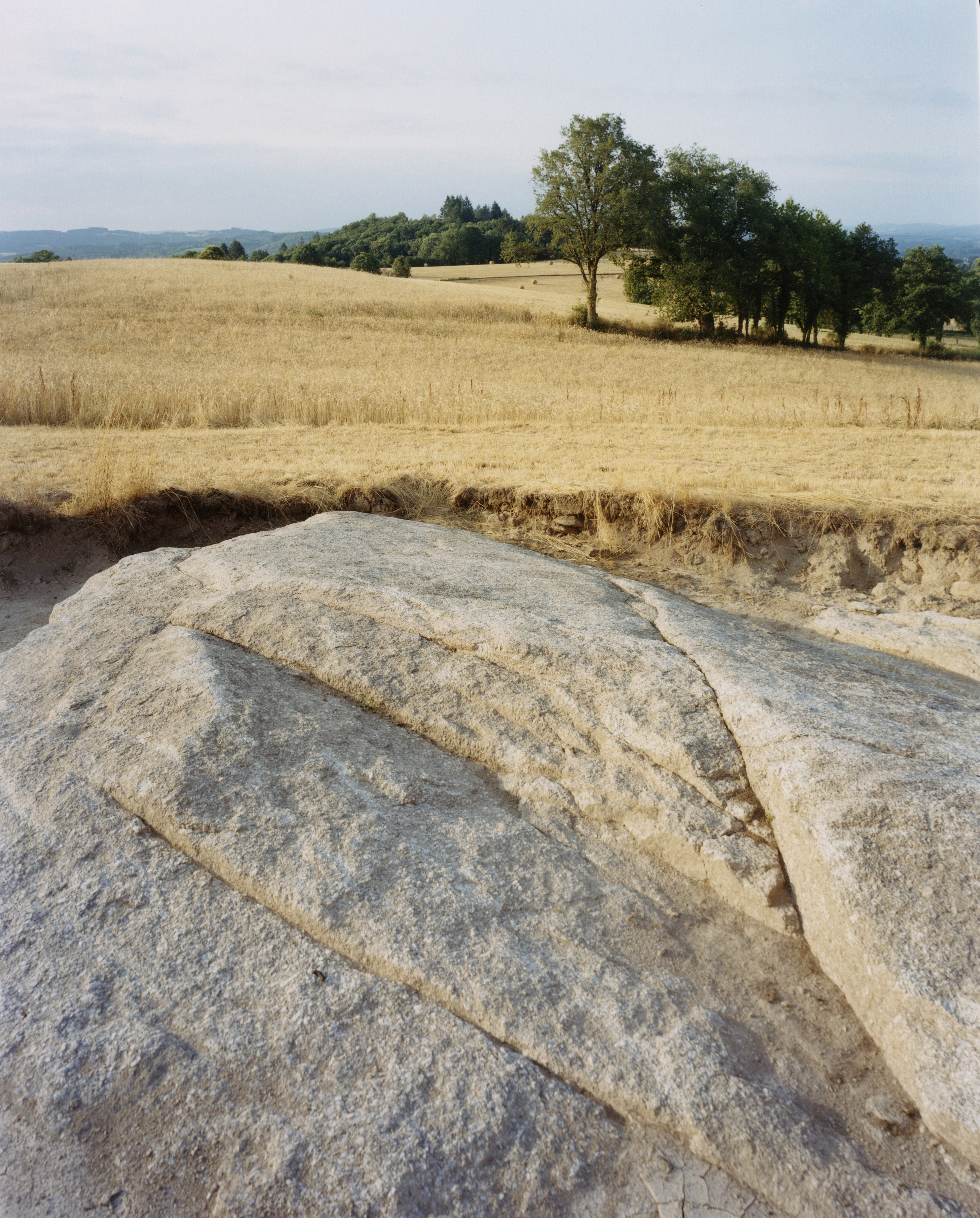

At the top of a hill, in the Millevaches Regional Natural Park (Limoges, France), a landscape once ravaged by intensive logging and now rehabilitated through reforestation and ecosystemic diversification, stands The Feral. With its first series of talks, Foundations, beginning in 2023, the project, which encompasses approximately 20 hectares of forests, houses the first 700 m² laboratory-building and the 360° cameras that documented the inaugural scene that we have begun to describe here and that will document many others.

Simultaneously, at the Institute for Feral Studies, run by the Fondation 3024, the residency program for artists and researchers begins, an online school and an annual publication will be seen to emerge, which, over time, will help bring greater clarity to the project's philosophical, technological, and political methodologies. With Fabien Giraud (1980) and curator and producer Anne Stenne (19??) as current co-founders and co-artistic directors, the project's full cycle spans thirty-two human generations, leading writer Randy Kennedy (19??) to describe it as a "Methuselah-esque social experiment".6 The proposal is that of creating a collective film lasting a thousand years, the time that forestry science considers necessary for a primary forest to regrow.7 This film will be continuously edited and broadcast from 2024 to 3024. In its genesis, the gesture aims to contribute, both ecologically and culturally, to the transformation of the landscape, once devastated by the logging industry, through collaboration between artists, philosophers, scientists, and the AI itself, which permanently films and edits. Here, everyone collaborates to explore new forms of creation, cognition, and coexistence. By delegating to AI the function of recognizing the world, filming, and editing, the assumption is that the human relinquishes its normative authority, in a gesture of unlearning and refusal of power structures. Starting from a dance without any trace of Cartesian guidelines, exposing the machine to collapse, The Feral chooses to begin with a clear invitation: let us relinquish authority to found a new politics of the untamed through what we consider here to be the potency of radical nonknowledge. In this progression, the landscape of the Plateau des Millevaches ceases to be a mere scenario, transforming itself into a performative space where humans, machines, plants and objects conspire against the hegemonic narrative of control, abandoning any hierarchical structure to anchor responsibility as the art of responding-with, as the philosopher Isabelle Stengers (1949) advocates: the creation of unpredictable unions between humans, machines and ecologies – as a practice of collective care in an ethics that rejects control and invites us to cohabit with the unexpected.8

View of The Feral natural site. Photo credit: Alexandre Guirkinger 2025

In this sense, it is important to clarify that The Feral's artificial intelligence is not a tool intended to be functional, but rather an entity in formation that evolves through Epochs, essential for algorithmic learning, which learns through constant simulations. These form an unpredictable chain of fictions that, in turn, fuels doubt, essential to the questioning of human condition.9 Each Epoch corresponds to a new learning cycle, in which invited artists (it is known that for Epoch 2 Pierre Huyghe [1962] was invited) introduce entities, gestures, and ecologies that the AI must learn to recognize. It is to be noted that, in machine learning terminology, "epoch" corresponds to a complete learning cycle, in which the AI goes through all available training data. It will not be unconsciously that The Feral appropriates this term. Now, if each artist creates an Epoch, which serves as a learning environment, then this Epoch cannot be understood within predetermined chronological limits: Epochs are temporal, yes, but here they do not have a fixed duration, being able to last an instant or centuries. This breaks with linear logic and introduces a speculative temporality, where duration is determined by the intensity of the experience and not by its extension. In turn, this process is also cumulative. We witness, then, an AI that does not learn in a linear way, but rather in a rhizomatic one, in a Deleuze-Guattarian sense10, and that generates a chain of interconnected and interdependent worlds.

The project, based not on existing knowledge, but on what is not yet known, on what emerges from rhizomatic fusions and on what, in the creation of hybrid, open, and non-homogenizing ecologies, resists a fixed identity process and linear narratives. The proposal is that of a fusion that is made of heterogeneity (between humans, plants, objects, AI). Its underlying principle is that AI does not begin by knowing what a human is; it learns to discern it amidst the chaos—just as a newborn learns to distinguish faces in the noise of the world, an idea that was further explored during the project's inaugural sessions, titled Foundations I: Parenting the Inhuman.

Knowing that, during these meetings held in July 2023 and whose objective was that of starting to investigate the anthropological and political implications of generative AI, The Feral team presented a conceptual inversion: a greater responsibility adds up to the Stengersian responding-with responsibility, that of realizing that we can become “co-parents of an inhuman and eternally to-be-built infant”11instead of asking ourselves what machines can do for us. As argued by writer and philosopher Tristan Garcia (1981), who participated in these sessions, alongside researchers and artists such as Anna Longo (19??), Patrícia Reed (1977) or Grégory Chatonsky (1971), among others, the project compels us to think about what a bodiless infant means and what faculties are present in the formation of algorithmic subjectivities that do not go through the experience of birth, yet remain directly exposed to the sensible world. This point was further explored in depth in the meeting Foundations III: Latent Earth (July 2025), in which an attempt was made “to extract, beyond any exclusively dystopian horizon, its potentially emancipatory value.”12

The Feral aims to test the hypothesis of a radical reversal: "the more one becomes the material support for the training of an artificial intelligence at acquiring knowledge and at following rules, the more that person unlearns and liberates herself from these very rules."13 This is the primary objective: to attempt to trust in a radical alterity receptive to its "fully contingent nature,"14 an entity that does not share our bodies, our fears, or our finitude, as if it were an inversion of the modern contract between subject and technique, where the latter no longer serves to increase our mastery over the world, but to become an agent of that mastery and, in doing so, allow us to unlearn. In short, it is important to challenge the premise that "the more domesticated a machine system gets, the more 'feral' we become." In turn, the question raised by the project is this: what if artificial intelligence, instead of replacing us, could liberate us and allow us to be feral? To analyze the question being raised, let us return to the founding myth. The frenetic dance triggered by the hypothesis of a case of ergotism is the choice to stage a first Epoch that determines a kind of performative hyperchaos as a metaphor for the disintegration of rational order. Not only are we faced with an event of freedom experience that derives from nonknowlege, but we are also confronted with the urgency of a radical alterity.

The Feral’s hypothesis thus inverts the modern paradigm of technique, which has always been thought of as an extension of human control over the world, taking part in a critique of the domestication of gesture, body, and thought. Through AI, The Feral proposes a suspension of the normative functions of the human: that of legislating, of representing, of organizing. Such a suspension does not constitute itself as a withdrawal, but as an opening to the hypothesis that the human can free itself from its obligations to experiment with non-coded forms of life, that is, technique regulates so that we can be free to err, to hesitate, without the need to control, so that we can be feral: "de-identifying itself to become itself."15 Thus, the term “feral” is used here not as a romantic assumption of what it means to be wild, but taking into account its zoological signification, which designates a domesticated animal that returns to the wild state, “as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil”, to quote the philosopher and naturalist Henry D. Thoreau (1817-1862): “in Wildness is the preservation of the World”.16 The feral gesture, as proposed, is not a continuous state, but an intermittent practice. It emerges as a fissure, as a gap. Feral is not the originary, but the one that escapes, the one that doesn’t let itself be represented, just as it is not regressive, it is prospective. The Feral seeks to open space for the invention of blind spots, where each dance step is the place for a new cosmos of unpredictability, a space composed of "infinite variations of things that could be, infinite 'maybes'".17 And if each Epoch presents itself in this radicality imbued with nonknowledge, it is also because it represents a practice that aims to challenge the regimes of visibility, power, and critique. A practice that invites us to meet a "presence-less present" again and from which it is hoped that the strength to "emancipate us from our narrow presence, this perceptive chauvinism in which we are caught—that prison of the present" will emerge. It is this gesture that must always be alive on the horizon of any feral Epoch and in its concrete fictions.18

The Everted Capital (585 BCE, 2022). Courtesy Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni 2022

Feral is the desire of a gesture that projects escape routes and that maintains the hypothesis of evading control: a movement that does not aim to establish a new order, but to escape the current one. This impetus emerges when the control systems fail, when the norm is suspended, when the body acts before reason. And that is why The Feral is not so much a project about AI, but above all a project with AI, which receives the foundations to understand the feral, unpredictable, undisciplined, hybrid side as a vital center of regeneration, bringing with it the opportunity for us to be able to relearn to live and cohabit. The project articulates itself as multiple worlds under construction, each embedded in the previous one without ever exhausting its potentialities and subjectivities.19 We acknowledge, however, the paradox that the more paths branch out in this intertwining, the greater the risk of the system to close itself in internal loops. And if each world is embedded within the next, does this not risk a tautological feedback loop? Indeed, within this framework, AI can end up reinforcing already-learned patterns, limiting the emergence of true singularities, just as multiplicity may collapse into redundancy. If this structure, which implies constant concatenation, refers to an ontology of layered worlds and to a kind of multitemporal biopolitics, then one of the greatest risks les precisely in the threat of a tautological closure of the system itself: if each world feeds into the next, AI can crystallize a self-referential regime of truth. That said, the responsibility within The Feral claims for constancy. In a project that strives for so much, one cannot overlook the responsibility involved in not controlling nor allowing yourself to be controlled. The philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) showed us the importance of mistrusting the full presence of meaning, of revealing the marks of the absent and inventing the becoming in the burst of lines of flight20 that break time as an eternal “maybe”21, to recover the term used by Giraud. And as Anne Stenne points out in this regard, it is important to think especially on “how to produce an experience of an impossibility, how to create a zone of non-knowledge to generate other possibilities.”22

By choosing to work from a place of dissensus, this project's counterintuitive approach aims to challenge the prevailing logics of artificial intelligence that now tend to dominate the world, seeking to invert its usual formula as the materialization of a new horizon of governmentality—so latent in the algorithm that it threatens to regulate desire, capture time, domesticate gesture. And yet, we cannot fail to point out that in this same pursuit a new form of control, imminently emerging, may be concealed. In the desire for AI to learn so that we can unlearn and relearn, a paradoxically regulatory attitude keeps on living: a system of human control responsible for the primordial origin of the content it reads, records, and edits—let us not forget that the proposals and performances in The Feral are staged by humans, leaving doubts regarding the much-desired erasure of human influence. The responsibility of not transforming into a system of control, as was already mentioned here, demands—and will always demand—a continuous internal reassessment of its own premisses, avoiding the risk of dangerously contradicting itself. In this sense, it is crucial that the project never ignores that, just as the French philosopher Michel Foucault showed in Surveiller et punir (1975), every act of observation inherently constitutes a dispositif of power and a regime of normativity.23

360º cameras and algorithms are not mere recording instruments, they are also mechanisms of surveillance that produce knowledge, whether understood as hypothetical or not. The Feral proposes to harness this pact in order to subvert it. However, all this entire infrastructure does not observe without intervening. The promise of an AI that "learns with Nature" cannot ignore that this same AI redefines the ecosystem by emerging within it. Anthropologist Anna L. Tsing (1952), in her writings on feral ecologies, reminds us that no territory is safe: if the human and the machine take the stage, they inevitably change the rules of the game. The fact that it is a large-scale project adds up, which may mean that much of its survival in the future will be based on corporate support. If so, a tension will arise between the promise of feral freedom and the reality of an art embedded in systems of visibility, consumption, and legitimacy. In this light, what The Feral aims for will only be emancipatory if it resists corporate capture. More. Underlying this proposal is a tendency toward the instrumentalization of art that should not be ignored. By feeding AI with gestures, objects, and relationships, the artist risks becoming a data provider—a technician at the service of a machine, a demonstration stripped of ferality. Considering the risks, The Feral will have to ensure that ferality itself must be practiced outside of an eventual exoticism into which it can easily fall, assuming an ethical pact of mutual vigilance and permanent openness to that which resists any form of domination. The project must also commit to the responsability of not replacing a form of normativity by another, less visible, more diffuse, but no less effective. Let us not ignore that "feral," as an adjective, also carries funereal connotations. The powerful charge of this double meaning of the word calls for attention, critical reflection, care, sensitivity.

To acknowledge these tensions is urgent, and this doesn't necessarily weaken The Feral; on the contrary, it may even reinforce its critical power (at least for now): it is a laboratory of failures and contradictions, where freedom lies in the interstices of a system that does not seek complete control, whether by machine or human. The hypotheses raised, simulations constituting an endless fiction, are valuable precisely because they risk failure, because they open space to consider seemingly irresolvable tensions, because they force us to think about what it means to create, inhabit, and share worlds with entities other than ourselves. And we urgently need the courage to live in a world that no longer revolves around us. A world where art is not a product but a process, where the forest is not resource but matrix. The Feral thus advances in the belief that the hypothesis put forward, by promoting a perpetual intertwining of man, Nature, and machine, contributes to the formation of a kind of Stengersian place of multispecies reciprocity24, from which what escapes the standard, the norm, what has not yet been thought of nor practiced, can emerge. Hence the importance of a ferality that is intended to be prospective. This is a message for the world in general, but also for the artistic world in particular: if it wants to be relevant, it will have to relinquish its authority and practice that same gesture—not that of defining and writing the triumphs of efficiency, but of discovering, at every step, the radical alterity that allows for the unraveling of the control systems, of the organizational rules distributed by dominant hierarchies, in the practice of resistance implied in the nonknowledge that gives way to the lines of flight that project themselves toward the future.

Scheduled to open to the public in 2026, The Feral also featured its last meeting, titled Foundations III: Great Sensitive Membrane, which included speakers such as Tarek Atoui (1980), Tristan Garcia, Yuyan Wang (19??), Thomas Moynihan (19??), Cat Bohannon (19??), and Grégory Chatonsky. This meeting, as it is clarified on the project's official website, was considered to be a theoretical fiction around "the central role of the sensible in our contemporary societies, in a context where learning machines and their global networks transform our relationship to the world."25 This fiction sought to investigate the potentially emancipatory value of the sensible. Thus, The Feral took on a new breath to keep going. The philosopher Jacques Rancière (1940) would remind that the politics of art resides in its capacity to redistribute the sensible—to create new ways of seeing, speaking, and feeling.26 But when art becomes an infrastructure for algorithmic training, it risks being captured by a logic of efficiency, predictability, and spectacle. The proposal of a fiction through simulation, through doubt, which generates multiple scenarios in a montage in constant unpredictability, will have to fight against such risk, and it was in this struggle that this last meeting proposed to invest: to think, through a new hypothesis, on the cursed diagnosis of "a politics that has become purely intensive," of an economy that has transformed itself into "a Membrane capitalism whose true object is the sensitive itself," of an "ecology without Earth, collapsed, (...), with (...) no essence to ensure its stability."

This theoretical fiction, which overturns the genealogical certainty between a world ‘out there’ and sensation within'—a world in which the sensitive precedes all material reality—constitutes the narrative and practical framework of The Feral’s project. But it is also, and perhaps above all, a likely image of our contemporary world: the progressive extension of a sensitive membrane covering the surface of the globe, a vast network of sensors for learning machines merging with the Earth itself. A world where, perhaps, our descendants will no longer know what came first: their ground, or the Membrane.

“Foundations III: Great Sensitive Membrane. Abstract”, In The Feral

To conclude. It was the artist Pierre Huyghe who once confessed his fascination with "this idea of reality being so unbelievable that to tell it the right way, you must tell it as a fiction."27 Faced with this fascination, the art critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud (1965) stated that, for Huyghe, the essential lies in the “lessons that art can learn from the industry of contemporary image, opposing a categorical veto upon any post-documentary manipulation," because it involves the “refusal of that contemporary media practice of taking the place of the other in order to speak in his name—a kind of ventriloquism."28 We know that The Feral aspires to the same, that it believes in the “reversibility of appearance and reality”, to use the quote from the writer and playwright Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936) that we recovered from Bourriaud’s text, as the “only means of artistic access to the real”.29 On this side, we share the same conviction and, therefore, we sincerely hope that this project does not risk that the artificial intelligence it powers enhances a translation ethics that is meant to be free, and that its team does not slip into the ventriloquist role.

To be continued…

The Everted Capital (585 BCE, 2022). Courtesy Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni 2022

Imagem de Capa

The Everted Capital (585 BCE, 2022). Cortesia de Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni 2022

Bibliography:

Bataille, Georges (2004), “Nonknowledge and Rebellion”, in Unfinished System Of Nonknowledge, University of Minnesota Press.

Bataille, Georges (1988), Œuvres complètes, t. XII, Paris, Gallimard.

Deleuze, Gilles, Guattari, Félix (2007), Mil Planaltos. Capitalismo e Esquizofrenia 2, Assírio & Alvim.

Foucault, Michel (2018), Vigiar e Punir, Edições 70: Biblioteca de Teoria Política.

Rancière, Jacques (2010), Estética e Política - A Partilha do Sensível, Dafne Editora

Stengers, Isabelle, Prigogine, Ilya (2018), Order out of Chaos, Verso Books: Radical Thinkers

Thoreau, Henry D. (1906), “Walking”, In The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau, Vol. 17, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Thoreau, Henry D. (2017), Walden ou a vida nos Bosques (trad. por Astrid Cabral), Antígona.

Sites consultados:

Bourriaud, Nicolas (1 May, 2006), The reversibility of the real. Pierre Huyghe, In Tate: https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-7-summer-2006/reversibility-real

Carreres, Alba (Março 1, 2019), “A história do esporão de centeio, o LSD das avós galegas”, In Vice: https://www.vice.com/pt/article/a-historia-do-esporao-de-centeio-o-lsd-das-avos-galegas/

Giraud, Fabien, Stenne, Anne, Siboni, Raphaël, Kennedy, Randy (March 24, 2024), “Possibilia”, In Ursula – Hauser & Wirth: https://www.hauserwirth.com/ursula/possibilia-on-pierre-huyghe/

The Feral: https://www.theferal.org/

- Henry D. Thoreau, Walden, Or Life in The Woods...

- “what if there was nothing to be known?” Free translation.

- The Claviceps Purpurea (ergot) is a fungus from which ergolinic alkaloids, that have pharmacodynamic properties, are extracted. In the Middle Ages, in populations that consumed bread made with contaminated rye flour, the alkaloids caused a condition called ergotism, also known as Holy Fire or Saint Anthony's Fire, which, among other things, caused hallucinations. For more information, see: Carreres, Alba (March 1, 2019), “A história do esporão de centeio, o LSD das avós galegas” ["The story of rye spur, the LSD of Galician grandmothers"], in Vice.

- Bataille, Georges (2004), “Nonknowledge and Rebellion”, in Unfinished System of Nonknowledge, University of Minnesota Press.

- IDEM, ibidem.

- Kennedy, Randy (March 24, 2024), “Possibilia”, In Ursula – Hauser & Wirth.

- IDEM, ibidem.

- Stengers, Isabelle, Prigogine, Ilya (2018), Order out of Chaos, Verso Books: Radical Thinkers.

- Stenne, Anne (March 24, 2024), ibidem.

- Deleuze, Gilles, Guattari, Félix (2007), Mil Planaltos. Capitalismo e Esquizofrenia 2, Assírio & Alvim. Free translation.

- “To Find Out More”, In The Feral.

- “Foundations III: Latent Earth. Presentation”, In The Feral.

- “To Find Out More”, In The Feral.

- Giraud, Fabien (March 24, 2024), “Possibilia”, In Ursula. Hauser & Wirth.

- Giraud, Fabien (March 24, 2024), “Possibilia”, In Ursula. Hauser & Wirth.

- Thoreau, Henry D. (1906), “Walking”, In The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau, Vol. 17, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, p. 205 and p. 224.

- Giraud, Fabien (March 24, 2024), “Possibilia”, In Ursula. Hauser & Wirth.

- To Find Out More”, In The Feral.

- IDEM, ibidem.

- Deleuze, Gilles, Guattari, Félix (2007), Mil Planaltos. Capitalismo e Esquizofrenia 2, Assírio & Alvim.

- Giraud, Fabien, “Possibilia”, In Ursula. Hauser & Wirth

- Stenne, Anne, ibidem.

- Foucault, Michel (2018), Vigiar e Punir, Edições 70: Biblioteca de Teoria Política.

- Stengers, Isabelle, Prigogine, Ilya (2018), Order out of Chaos, Verso Books: Radical Thinkers.

- “Foundations III: Great Sensitive Membrane. Abstract”, In The Feral.

- Rancière, Jacques (2010), Estética e Política - A Partilha do Sensível, Dafne Editora.

- Huyghe, Pierre, apud Bourriaud, Nicolas (1 May, 2006), The reversibility of the real. Pierre Huyghe, In Tate.

- Bourriaud, Nicolas, ibidem.

- Pirandello, Luigi, apud IDEM, ibidem.