Music for the End of Times

In recent decades, the accelerated collapse of planetary structures due — mainly, but not solely — to the imminence of environmental devastation has compelled humanity to face an explicit level of existential risk. Among the humanities, especially philosophy and the arts, it has become almost commonplace to assume the inevitability of human extinction: everywhere, it has been necessary to realize, gradually and then suddenly, that the world has already ended. Taking from the post-media manifestos of the 1980s and the more laughable perspectives on the end of history in the 1990s, to various science fiction predictions and their limitations to a “capitalist realism” in the 2000s and 2010s, including here also the recent and somewhat refined theses (albeit deeply divergent) of Moynihan, Wallace-Wells, or Kopenawa, cinema, painting, dance, and literature have reverberated this certainty in an apocalyptic future. Today, atmospheric notions of a generalized crisis saturate the exhibition texts of museums and biennials with comfortable clichés and soft threats, as if these institutional media had any significant role to play in the catastrophe that awaits us — as if collapsologists were now all throwing up their hands to the sky wondering what artists and curators would say, those heroic carriers of the Earth.

Music, however, remains strangely detached from this context, from these pretensions. It either struggles to piece together the fragments of a critical and politically proactive position that could shine through in its program of normally hyper-abstract themes, or seeks to deny its own connection to other arts, convinced that the end of the world should not come for itself — for others, yes, but for others only. Part of this detachment can be explained by the very genesis of music as a field, separated as it was in the Quadrivium (and before that, in transversal Greek notions such as beauty, technique, theory, catharsis, and eroticism) from the ars mechanicae of medieval artisan guilds. Beyond this historical origin, in closer connection with pure mathematics and the objectivity of ideal forms than with the construction of practical plasticities and perceptual pleasures, music also seems to be directed toward a productive self-sustain that definitively distinguishes it from the economic and moral failure of the other arts. There seems to be no room for the apocalypse of the arts in music because music, both in its institutional and market aspects, is still doing very well, thank you, in terms of its viability, or in terms of the flow of capital that guides and stimulates it.

Another factor distances music from contemporary debates about the end of the world, not due to merit, but lack: its total unsuitability (and unwillingness) for homologous representation and immediate fruition. That is, what can sound do in this context of the undoing of everything we know? If cinema and painting produce images of other futures, allowing new ways out of annihilation through the malleability of the senses; if literature and theater simulate evaluative grammars linked to behaviors, events, and trajectories in order to intuitively rework them; if architecture and dance can design ambiences and landscapes based on human gestures, revealing their profound executory power,... Music is limited to evoking rhythmic modules and pulsating frequencies that, at best, produce therapeutic sensations, or else define transcendent temporal cycles that escape us and which we can only contemplate in ecstasy. Even if we analyze, like Attali or Tomlimson, music as an anthropological technology that emerges before language and epitomizes culture, the transmission of heredity, and the collective organization of mnemonic patterns, it still falls short of other arts, as it now seems uncontrollable, a vector resulting from complex evolutionary ecologies and non-linear arrangements, rather than an intentional tool for dealing with anything, let alone something as multifaceted as universal ruin.

I propose, though, that music has a special attribute for metabolizing the apocalypse, which remains only latent in its uses so far, and which can open us up to an almost schizophrenic optimism as a weapon against the current apologetics of decline. This is because music, in comparison with other arts, postulates a greater proximity between catastrophic time and messianic time, in exactly the way that was suggested by some radical theologies. “Apocalypse,” after all, means only “revelation,” and monotheistic eschatologies propose this charismatic renewal based on the final judgment and the passage to a new era. In the heterodox Christian thought of Teilhard de Chardin, for example, the end of the world is called the “Omega Point,” a stage in history in which a “noosphere” would emerge from the integration of technical and biological intelligences, in a kind of psychozoic split with nature. In Bultmann's existentialist Protestantism, as in Benjamin's Kabbalistic Marxism, the apocalypse is not a cosmic event but a continuous, minuscule, retroactive unveiling of the extreme openness of life by the beings who commune in it.

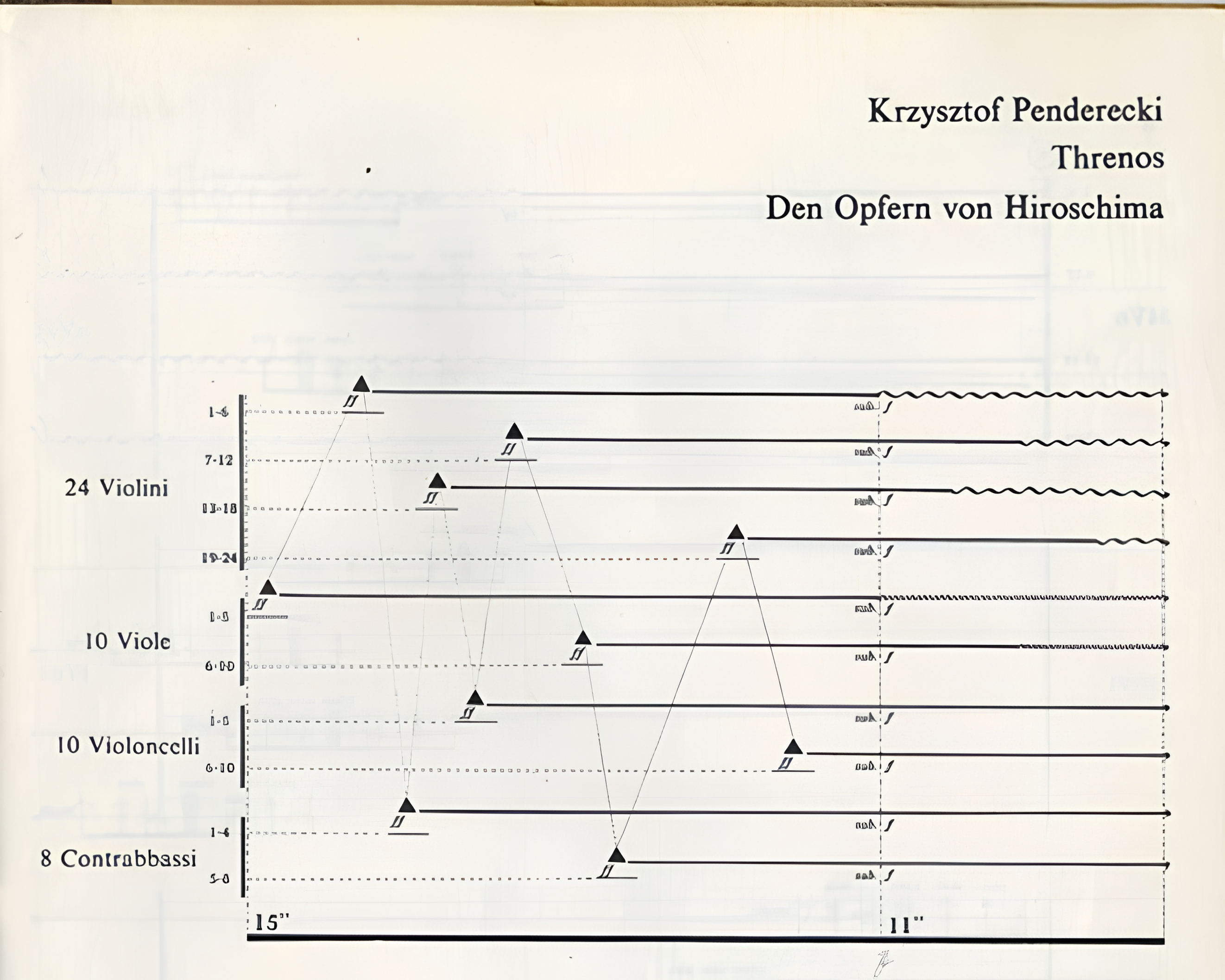

Music may be perfectly suited to this more holistic understanding of the end of the world — that is, to its acceptance. Although it cannot address or delay the end, it is, after all, the only artform widely recommended for funerals. Indeed, a decade after the atomic bomb, Krzysztof Penderecki would conceive one of the most claustrophobic pieces in the Western canon, “Threnos: Den Opfern von Hiroshima,” a study of integral dissonance in texture and volume, as a direct reaction to the Japanese tragedy. Modern conflicts and genocides have also been widely eulogized, as in Schoenberg's cantata for the victims of the Holocaust or Shostakovich's symphony about the siege of Leningrad. Not to mention pop music and its excitability to material culture, its metaphysical unobstructedness to that same apophantic field where disaster unfolds in real time. Critic Evan Eisenberg once wrote that rock n’ roll is the musical equivalent of a car accident; in the same vein, we can try to think of how deeply connected the musical subcultures of the last fifty years are to, for example, the AIDS crisis or the attack on the Twin Towers.

It is as if music could envelop the massacre in a certain kind of beauty. After all, it is music that comes to the rescue when words fail, filling the negative void of mourning with the positive void of the ineffable and allowing for a minimally honorable aestheticization of real and total death, which in other arts would be trivialized. The violins play as the ship sinks, and through these violins the shipwreck is redeemed. On several occasions, music has lent itself to the sketch of an incorporeal and amoral apocalypse, or of a catastrophe that could approach, animically and by its own virtues, messianic supra-reality. It is no coincidence that Olivier Messiaen composed his “Quatuor pour la fin du Temps” while a prisoner of war and from an unusual biblical reading, which inspired him to the vision of an angel descending at his feet to announce the abolition of time amid divine mystery. In this case, the composer's religious mysticism would open up for him, through his music, the image of a world without causality, without incompleteness, fulfilled with plenitude, even if not leading to an explosive disappearance, as in the historical apocalypse. Faced with the actual apocalyptic moment, music would rather, then, transfigure everything that this apocalyptic moment has of explosive disappearance into an image of a world without causality, without incompleteness, fulfilled with plenitude, etc.

The person who best articulated this relationship between eschatology, utopia, liturgy, and sonography was probably Ernst Bloch, the fabulistic communist for whom myths, dreams, and fantasies were pre-appearances of the more-than-perfect kingdom to come (that is, communist society). Religious ideas of paradise, surrealist aesthetic delusions, ancestral ritual symbolism — all of this would be nothing more than a laboratory for the seeds of processes and figures proper to utopia to discreetly anticipate themselves and fervently impel us toward them. In this scheme of declared “immanentization of the eschaton,” one starts from the non-negotiable principle of a glorious future, and then traces the reverse engineering of our ways of being as effective preparations for the approaching victory. Music, that Beyond encrypted by sound spots in the fabric of the Present, would thus become an antidote to despair or to the belief in a meaningless catastrophe, for it would be evidence itself of a gradual entelechial molding of civilization into a state of absolutely necessary culmination, which its resonant transcendence would foreshadow. It is not that music persuades, controls, or mitigates the apocalypse as other arts attempt to do, nor that it carelessly distances itself from the debate that this apocalypse imposes. What music can do best, what it actually does, is teach a euphoric resignation or blind confidence that the apocalypse is, in fact, phosphorescent, even in its most absurdly tragic aspects.

Perhaps in the coming years music will be forced into these apocalyptic discourses of which, I believe (and question, and suggest, and beg), we are all tired. There is an end of the world internal to sounds and their proportions that seems to occur at the edges of music without being perceived from its center, corroding it from outside in. These changes pose a crucial challenge to sound art, demanding the same mundane eschatological anxiety from it. Consider, for example, the experiments being conducted in acoustic transmission between non-human conversational agents, or the listening platform radio stations filled with songs recorded by generative artificial intelligence. Consider infrastructural music, which no longer serves the obligation of consumption and appreciation, nor interfaces artist and audience, but fills borderline factory spaces, archives never-witnessed interactions, or serves as a weapon for dispersing protests and torturing penitential subjects. These internal deserts of music — or, for now, just sound — might grow around it and slowly devour it. Until then, however, music will be assigned the most comfortable role in the apocalypse, which has always been its obvious one: that of trumpet. It will be up to music to announce, one by one, the anointings, and to comfort the sick by confirming that there is something waiting for them on the other side, for at the end of the world lies, like a twisted melody, its beginning.

Image: Krzysztof Penderecki, Threnos: Den Opfern von Hiroshima, score excerpt. © Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG

Rômulo Moraes is a Brazilian writer, sound artist, and researcher. He is a PhD candidate in Ethnomusicology at the CUNY Graduate Center with a Fulbright/CAPES scholarship and holds a Master’s degree in Culture and Communication from UFRJ. He is the author of “A fauna e a espuma” [7letras, 2023] and “Casulos” [Kotter, 2019]. He teaches at Bard College, Brooklyn College, Queens College, and the New Centre for Research & Practice. His essays and reviews have been published in journals such as e-flux, The Wire, The Brooklyn Rail, Aquarium Drunkard, and The Whitney Review, among others. His current interests include the phenomenologies of imagination, the entanglement of pop and experimental music, the cosmopoetics of prospecting, and the concept of “vibe” as an aesthetic category.