A GUEST + A HOST = A GHOST—so goes a famous pun by Marcel Duchamp, printed on the tinfoil wrappers of candies distributed at the opening of Bill Copley’s 1953 exhibition in Paris. Beyond the amalgamation of letters, the joining of these opposing words––the host who provides hospitality and the guest who receives it––results in their mutual annihilation. The phrase takes on even greater humour and meaning when inscribed on a candy wrapper: once the candy is eaten, only the wrapper remains, a shroud or ghost of the now-annihilated substance.

Something similar happens in the biological cycle of the parasitic fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis. The fungus parasitises the larvae of moths found underground on the Tibetan plateau; after germinating inside the larva, the cordyceps kills and mummifies its host, eventually emerging through the head and sprouting from the soil, not unlike the surrounding vegetation. In Chinese, it is called “DongChongXiaCao,” and in Japanese, “Tockukaso,” both meaning “winter worm, summer grass.”

For centuries, cordyceps has been a staple in Chinese medicine, believed to have tonic-reviving properties that boost energy, stimulate the immune system, and improve physical endurance. It is also said to treat numerous ailments, from cancer to erectile dysfunction. Awareness of the fungus’s miraculous properties spread to the West only in 1993, after athletes Wang Junxia and Qu Yunxia shattered world records at the Chinese National Games in Beijing. Their coach, Ma Junren, attributed their success to the properties of cordyceps.

Although its effects on humans remain largely unknown, demand for the portentous “Himalayan Viagra” has skyrocketed, especially in China. This surge in popularity has caused its price to rise exponentially as well, further exacerbated by scarcity and climate change. Each spring, local farmers risk harsh environmental conditions to harvest the fungus, with its unbridled trade leading to a host of nefarious consequences: environmental disruption, ecological imbalance, local disputes, escalating crime, and inflation in local economies. Today, most cordyceps on the market is cultivated through fermentation technologies, which have a negative impact on local communities, reliant on its wild harvest as their main source of income.

Diana Policarpo’s fascination with hybrids, with metamorphosis occurring within the natural realms, with the invasion/contamination of bodies, with physical transformation and the stories surrounding it––from myth to cyborg––is present throughout her practice. The process of transformation the artist focuses on is often invisible––due to the action of bacteria, viruses, genetic mutations or parasite fungi. However, her work does not merely reveal these metamorphoses; it also exposes their cultural, political, economic, social and anthropological implications. Or rather, the work shows how these processes and their outcomes resist common definitions and classifications, challenging the socially imposed categories we usually operate within.

A key element that exemplifies the artist’s approach is the fungus, present in the several bodies of work that she has been developing over the years. In order to define the complexity of this research, the different spheres of knowledge involved, its multidisciplinary development, and its resistance to classification, one could resort to the metaphor of mycelium. With the same rhizomatic pattern, Diana Policarpo’s thinking draws parallels between the interconnectedness of fungal mycelial networks and human relationships and societies, opening them up to a cosmic dimension.

Just as mycelia form vast symbiotic networks for nutrient exchange and communication, humans are also interconnected through relationships and shared experiences. This perspective encourages a shift from individualistic thinking to a relational understanding of self and the world. The vast network of mycelium highlights the interconnectedness of all things, both living and non-living, suggesting that individuals are inherently part of a larger whole.

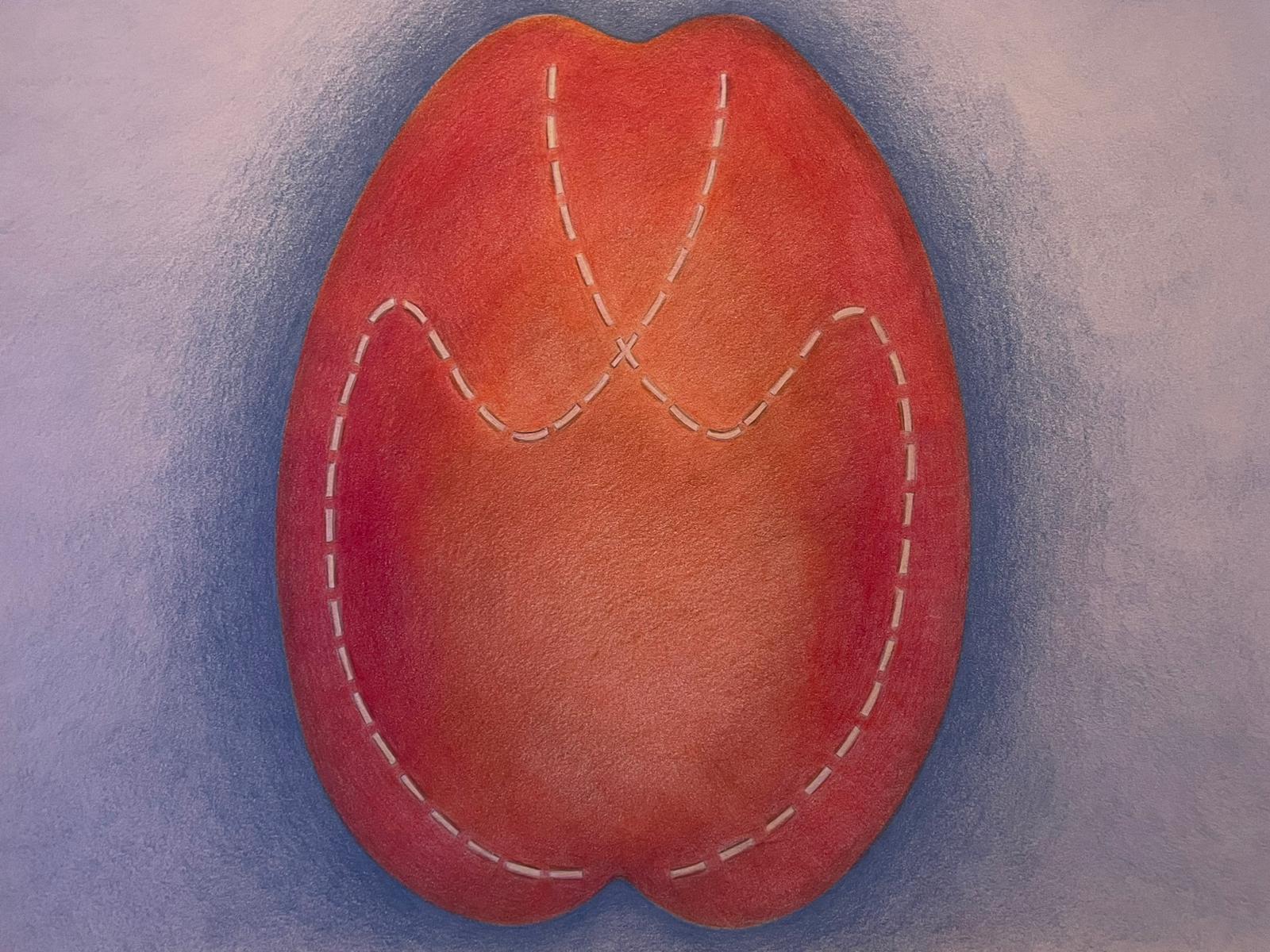

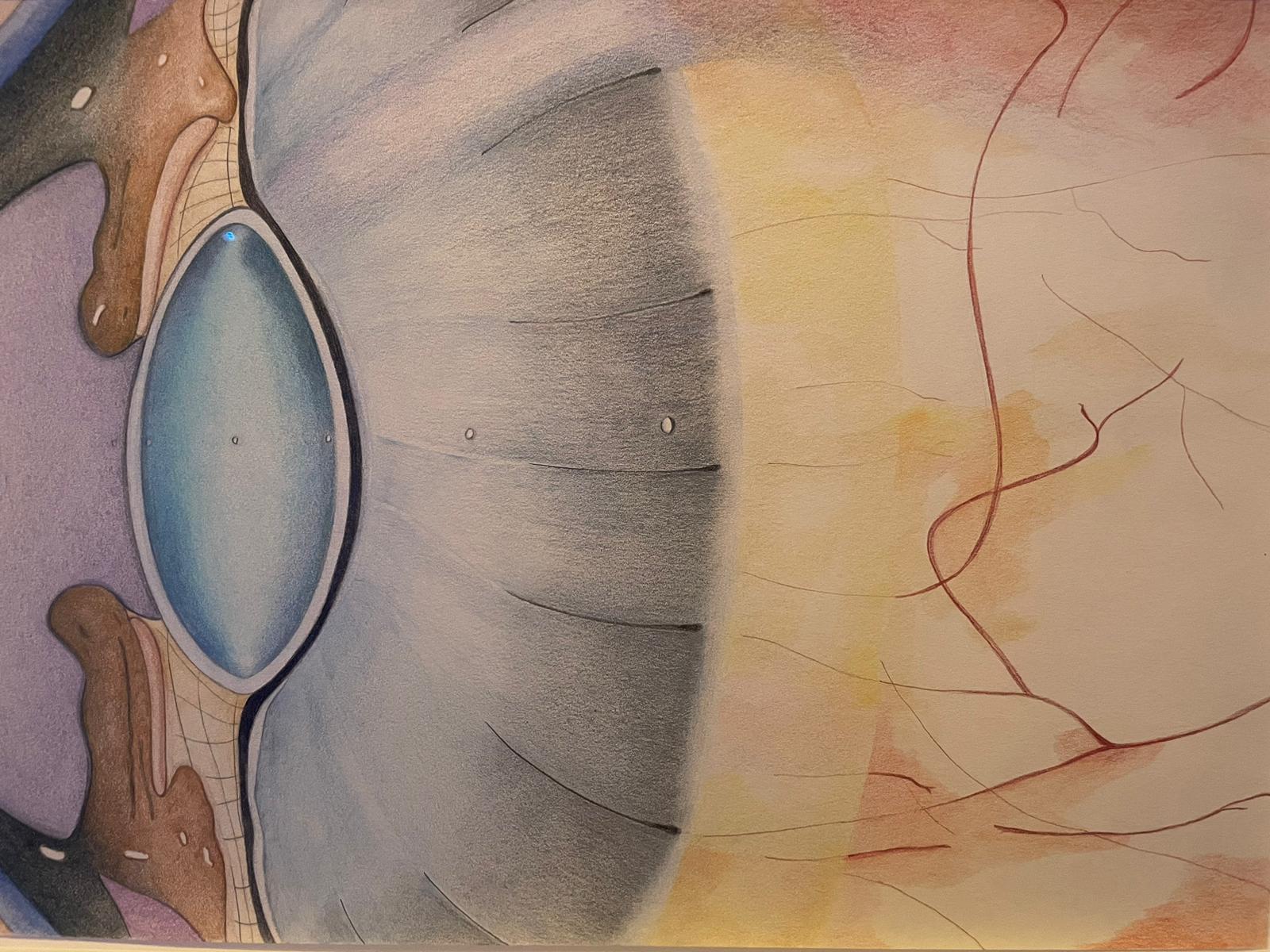

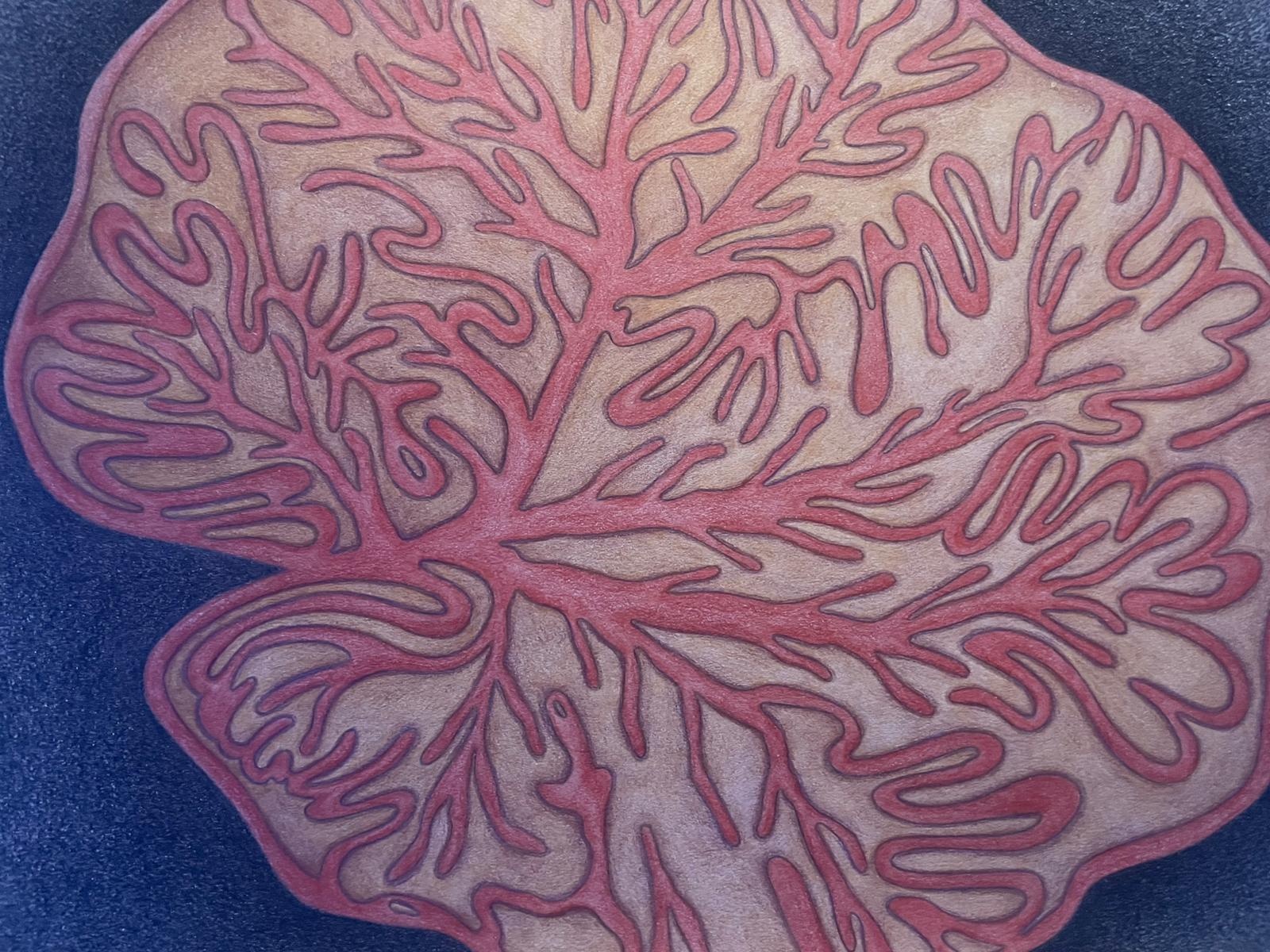

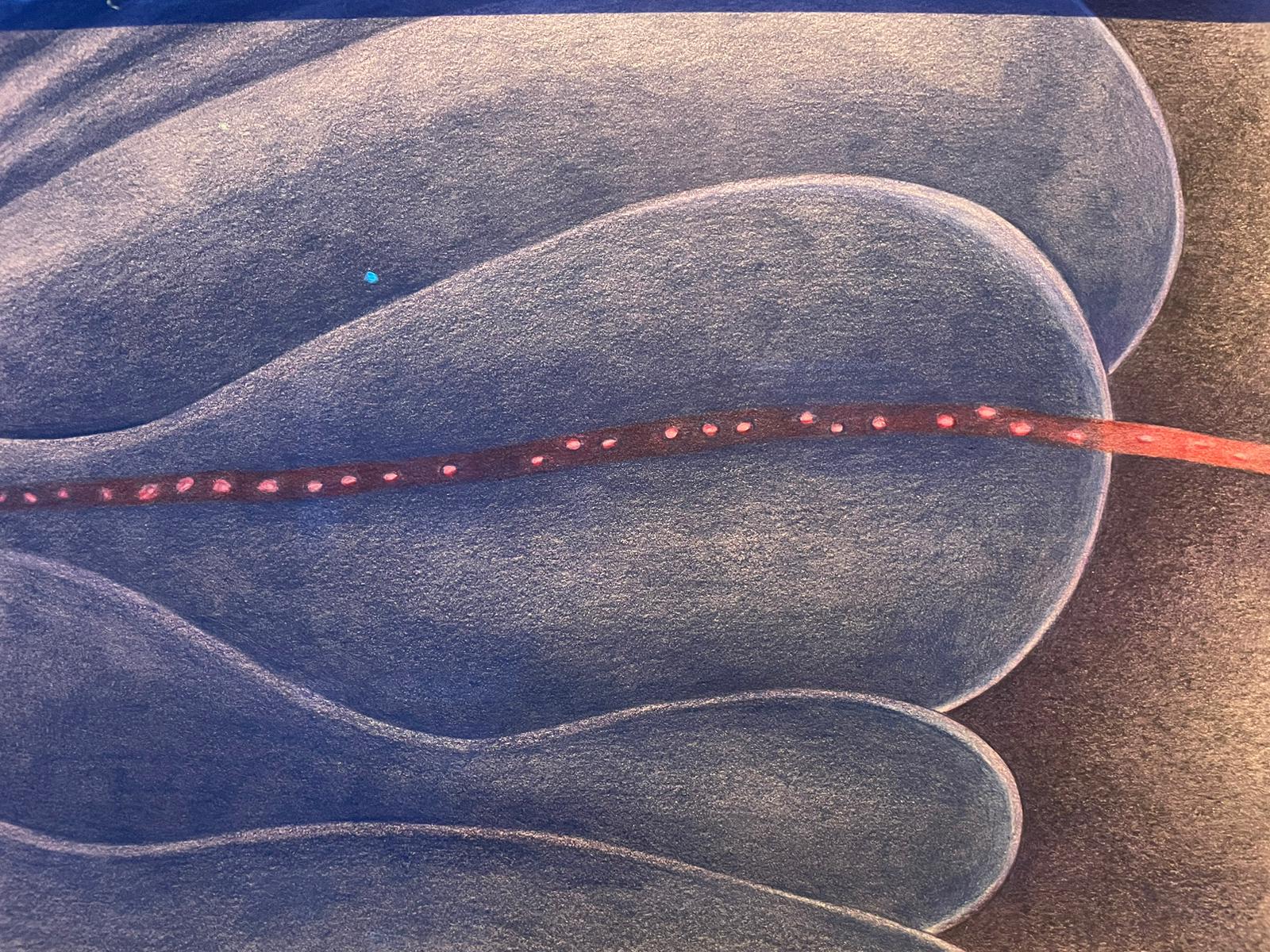

Diana Policarpo, Underground Allies. Photos © Vasco Stocker. Courtesy of the artist and Rialto6.

The artist’s installation Fungal Highways (2024), presented in Mutual Benefits, her solo exhibition at Rialto 6 in Lisbon (2024–2025), is the result of her research on cordyceps and embodies this essential interconnectedness. It consists of a 3D animation in which scientific depictions of the rhizomatic structures of human neurons seamlessly alternate with intricate mycelial networks of fungi. These intricated images flow in a circular projection on the ceiling, resembling a large open hole. The position of the projection invites visitors to recline on the platform on the floor, sprinkled with neuron-shaped pillows, and look at the frenetic activity of subcutaneous and synaptic worlds. The vibrating sound contributes to the slight hypnosis into which one falls while observing this eye, wide open in the ceiling.

Emanuele Coccia, in his various studies, focused on a concept of contiguity, fluidity, and intermingling of the elements of the existing world which can be likened to Diana Policarpo’s approach.1 Paraphrasing the philosopher’s words, metamorphosis is described as the phenomenon that binds all species and unites the living with the non-living. Bacteria, viruses, fungi, plants, animals––they are all part of the same life, and share the same substance.

A similar symbiosis between beings of different natures is hinted at in the series of pastel drawings Underground Allies, which the artist initiated in 2024. These detailed images, reminiscent of scientific plates, juxtapose anatomical sections and microscopic visions, drawing connections between the mechanisms of the human body and those of other organisms as they underscore a common substratum of the different manifestations of the world: the presence of a shared molecular language. Scientific language dissolves its rigour in the poetics of the interconnectivity and correspondence of things.

But Diana Policarpo’s references to fungi also yield more prosaic outcomes. The video ¥€$! (2024) loops a sequence of brilliant Chinese commercials promoting the precious cordyceps––the “Himalayan Viagra”—in ways tailored to Chinese and Western consumers.

Offering a counterpoint to the irony of this work is Summer Grass Winter Worm (2024), a short video documenting the fungus’s harvest on the Tibetan plateau. Undertaken under harsh conditions by some of the most marginalised classes, the process relies on local communities with ancestral knowledge, who are able to distinguish the fungus’s stem from the plants’. This video raises questions about environmental issues related to the growing cordyceps market and the impact of capitalism on the landscape and local daily life.

The harsh working conditions associated with the race to harvest this resource, driven by increasing market demand, were also addressed by the artist in the project Death Grip (2019), presented at MAAT as part of the Prémio Novos Artistas Fundação EDP. A multimedia, site-specific installation featuring 15-channel synchronised audio and two digital animations, Death Grip is complemented by an immersive environment consisting of sculptures, a lower temperature, and cold lighting meant to simulate the discomfort of working on the plateau.

“It is a place that is not necessarily pleasant to be in,” the artist explained, “but one that confronts the viewer with a reality that is both human and alien: the former personified by the work of the women who harvest and exploit the cordyceps fungus, and the latter by the behaviour of the fungus itself, the way it expands and takes over the space and its host.”2

The connection between fungus and women as repositories of traditional medicine and herbal ancestral knowledge is the focus of Nets of Hyphae, an exhibition presented at the Galeria Municipal do Porto and at Kunsthall Trondheim (2020–2021), curated by Stefanie Hessler. In this case, Diana Policarpo turned her attention to Claviceps purpurea (ergot), a parasitic fungus of rye, exploring its toxic effects (ergotism) as well as its medical uses in the context of traditional women’s practices. For example, ergot was used to induce labour, reduce postpartum bleeding, or terminate pregnancies.

In this exhibition, the artist created a speculative, tangled narrative that links the collective phenomena of hallucinations caused by ergotism to historical cases of witch hunts, suggesting that many accusations may be rooted in episodes of collective food poisoning. Through videos, sounds, voices, and drawings, Nets of Hyphae highlights how in the past the ergot fungus represented not only a toxic agent but also an intricate junction between patriarchal power, control of female bodies, and persecution of “marginal” figures, such as witches or folk healers. Simultaneously a toxic and healing substance, ergot becomes a vehicle for exploring power, gender, and bodily autonomy, pointing out how women’s medicinal use of ergot was demonised: the very practices that fostered female reproductive autonomy were stigmatised within narratives of witchcraft and patriarchal order.

In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson explores the queerness of pregnancy, challenging traditional notions of gender and family. She questions whether an experience that is so intensely personal and profoundly transformative can also be inherently conformist. The author examines how pregnancy can be a site of both radical intimacy and alienation from one’s own body, and how it can disrupt traditional narratives of gender and identity: “Is there something inherently queer about pregnancy itself, insofar as it profoundly alters one’s ‘normal’ state and occasions a radical intimacy with––and radical alienation from one’s body? How can an experience so profoundly strange and wild and transformative also symbolize or enact the ultimate conformity? Or is this just another disqualification of anything tied too closely to the female animal from the privileged term (in this case, non-conformity or radicality)?”3

Thanks in part to Silvia Federici’s studies, we now better understand how the regulation of women’s sexuality and reproductive capacity served as a necessary precondition for the establishment of more rigid forms of social control.4 The author proved how the witch-hunt served to “deprive women of their medical practices, forced them to submit to the patriarchal control of the nuclear family, and dismantled the holistic conception of nature that until the Renaissance had placed a limit on the exploitation of the female body.”5. In another text, the philosopher wonders: “Why were the witch hunts primarily directed against women? How does one explain the fact that for three centuries, thousands of women in Europe became the personification of ‘the enemy within’ and of absolute evil?”6

The definition of “enemy within” also fits well with that of the parasitic fungus, which attacks, alters, or kills its host. By touching different keys, the works of Nets of Hyphae also emphasise a connection between poisoning and possession: both are invisible processes, and describe a moment in which the self is “interrupted” by an alien force. Whether spiritual or chemical, the invading agent displaces the body from itself, turning it into a terrain of uncertainty, transformation, or threat. In this sense, the toxic or possessed body becomes a symbol of instability and resistance—something that cannot be fully controlled.

A further example of hybridisation of a female body appears in the video Adaptogens (2024). Here, the voice of a female scientist accompanies a poetic visual essay, juxtaposing laboratory scenes, microscopic views of mycelia and neurons, plants, fungi, planets, and space travel. This fictional tale, inspired by a conversation of Diana Policarpo with an astromycologist based in Macau, sparked the artist’s sci-fi imagination. Speculating on the possibility of life in space, the video examines the synthetic production of the active ingredient of cordyceps in microgravity, before the narrator begins to experience strange transformations in her own body. As if experiencing a personal “space oddity,” the narrator evokes a dissolution of identity in favour of a fusion of machine, fungus, and body. Languor is replaced by a positive feeling of becoming a new organism—a melding of identities, a harmony between life and technology.

Through fungi and mycelia networks, Diana Policarpo’s work revels in its power to make us question our systems and categories, thereby changing the way we think and imagine. In the parasitic fungus’s mechanisms, the artist found a language to critique both social and economic power structures while identifying repetitive recurring patterns of normativity. At the same time, the fungus and its spores, capable of infecting or fertilising, intoxicating or healing, of being reborn from a corpse or ghost, literally and fictionally open up interspecies perspectives for the survival of humanity, or alternative forms of life—on planet Earth, or somewhere else.

Cover Image

Diana Policarpo, Underground Allies. Photos © Vasco Stocker. Courtesy of the artist and Rialto6.

- Emanuele Coccia, The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture, trans. by Dylan J. Montanari, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2029 (2017); Emanuele Coccia, Metamorphoses, trans. by Robin Mackay, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2021 (2020).

- Ana Cabral Martins, “Explorando o Death Grip vencedor de Diana Policarpo, no MAAT,” Público, 4 July, 2019. Online: https://www.publico.pt/2019/07/04/culturaipsilon/noticia/ciclo-fungo-exposicao-maat-1878753 (accessed 20 June 2025).

- Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts, Minneapolis: Greyford Press, 2015, pp. 13–14.

- See Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, New York: Autonomedia, 2004.

- Silvia Federici, Caccia alle streghe, guerra alle donne, Roma: Nero, 2020, p. 21.

- Silvia Federici, Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women, Ostfilder: Hatje Cantz, 2012, p. 5.