Philosopher Achille Mbembe frames the plantation as one of “the first instances of biopolitical experimentation,”1 where nature, land, and human labour became commodities through violent regimes of control. In Necropolitics (2019), he expands on how this economy was a laboratory for extractive and racial capitalism in Africa: “The plantation is indeed a ‘third place’ in which the most spectacular forms of cruelty have free rein, whether it comes to injuring bodies, torture, or summary executions.”2 This blueprint of colonial logics, based on separation and classification, normalises the enslavement of fellow human beings. The enslaved person’s life was owned and kept in a constant state of exhaustion, depletion, and disposability.

Plantationocene, coined by anthropologist Anna Tsing, is the ecological regime birthed by colonial monoculture systems like palm oil, sugarcane, and coffee. In the plantation, any behaviour not directly translatable into profits is ruled out. This engine of European expansion, essential for capital accumulation in the West, has been imposed on people, animals, plants, and landscapes through all forms of violence, advancing capitalist and ecological devastation. Colonial economies have structured human and environmental exploitation matrixes that the post-colonial world has inherited and Western powers have maintained. Alarmingly, monoculture and modern-day slavery continue to proliferate, mostly run by Western companies in former colonies.

One such outrageous instance is the situation in the present Democratic Republic of the Congo. The southwestern province of Kwilu and its palm tree forests have since immemorial times yielded oil palm to the local communities, who employ it in multiple ways. This ancestral resource became a curse once the colonial enterprise set its greed on cheap vegetable oil. In 1911, during the Belgian colonial rule, the British soap company Lever Brothers received a concession of 750,000 hectares across the Belgian Congo to develop plantations and established the subsidiary Huileries du Congo Belge (HCB), later renamed Plantations Lever au Congo (PLC), and under ex-President Mobutu Plantations Lever du Zaire (PLZ). The HCB gradually expanded its land grabs and started planting seedlings to increase production of coconut and palm oil.

The plantations were essential for Lever Brothers’ global enterprise, which by 1930 employed 250,000 people and, in terms of market value, was the largest company in Britain. They remained central to the business when that year it merged with the Dutch company Margarine Unie, forming the Anglo-Dutch conglomerate Unilever. Arguably the first modern multinational company, it is still today an international food and consumer products giant. Yet Unilever’s website is oblivious to this part of their history, merely mentioning the plantations’ establishment years.3 This erasure reflects a widespread refusal by former Western colonial powers, in both public and private spheres, to acknowledge the atrocities that fuelled their unprecedented accumulation of financial and cultural wealth. In this coordinated concealment, they also erase the labour and the people on whose backs and through whose deaths entire fortunes and institutions were built.

The plantations used forced labour within a system of coercion. While the white British employees at Lever Brothers enjoyed dignified lives in the renamed Leverville, past and present Lusanga, African workers—the legitimate landholders—endured atrocious conditions and degrading treatment. Many were recruited from other regions and heavily exploited, forced to perform dangerous tasks like climbing high tree trunks to pluck heavy bunches of palm nuts while fires were set at the base. They endured whipping. Children were also forced to work. During the economic crisis of 1929, starvation wages were further reduced, and the town of Kikwit saw the largest anti-colonial uprising in 1931. The Pende revolt lasted four months. A brutal crackdown ensued, with more than 1,300 Africans killed.

At the time, a Pende sculptor created a 60-centimetre high wooden effigy of Maximilien Balot, a white colonial administrator who was investigating the rape of a Pende woman by a Belgian recruiter of palm nut cutters. Balot was beheaded in a clash, and the statue was made to subdue his evil spirit and protect the local community. In 1972, collector and political science professor from New York Herbert F. Weiss bought the sculpture in Belgium for 700 USD. He sold it in 2015 to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) in the United States for 24,000 USD. Chief’s or Diviner’s Figure Representing the Belgian Colonial Officer, Maximilien Balot (around 1931) travelled widely before finally returning home, albeit temporarily, in 2024. It has become a symbol of resistance.

This restitution was orchestrated by the Lusanga-based Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC, Congolese Plantation Workers Art League), a cooperative of artists, mostly former and current plantation workers from various regions, founded in 2014 with environmental activist René Ngongo, the founder of Greenpeace Congo, who now presides over CATPC. The collective comprises nineteen artists. The website lists founding members, recent members, and trainees: Djonga Bismar, Alphonse Bukumba, Irène Kanga, Muyaka Kapasa, Matthieu Kasiama, Jean Kawata, Huguette Kilembi, Mbuku Kimpala, Athanas Kindendi, Felicien Kisiata, Charles Leba, Philomène Lembusa, Richard Leta, Jérémie Mabiala, Plamedi Makongote, Daniel Manenga, Mira Meya, Emery Muhamba, Tantine Mukundu, Olele Mulela, Daniel Muvunzi, Alvers Tamasala, and Ced’art Tamasala.4

CATPC worked for a decade in close collaboration with the art institute Human Activities (HA), initiated in 2012 by Dutch artist Renzo Martens and which started the sculpture workshops that soon gave rise to CATPC. HA’s two-day opening seminar took place in Boteka, DRC, on a palm oil plantation, gathering Congolese and international art historians, philosophers, climate activists, architects, urbanists, economists, anthropologists, and artists to discuss the history of the plantation, gentrification, and the role that art can play. CATPC embodies a belief in art as a tool for change. They began producing conceptual sculptures in clay, 3D scanned and reproduced in cocoa and palm oil in Amsterdam (the world’s largest cocoa port), or 3D printed in cream colour, to be exhibited and sold internationally. Proceeds are used to purchase degraded land and repair it through regenerative agriculture. This post-plantation, or anti-plantation, is everything the plantation is not: egalitarian, biodiverse, sovereign.

After independence in 1960, Unilever’s productivity in Congo declined due to Southeast Asian competition and Mobutu’s confiscations of foreign businesses in the renamed Zaire. Unilever resumed palm oil production in 1977 for the domestic market. Still, profits dwindled, and the company gradually disengaged from the DRC after two civil wars between 1996 and 2003, leaving completely by 2009 and selling the remaining lands to a Canadian hedge fund.

Lusanga’s plantations and facilities were abandoned three decades ago. Villas and offices are overgrown, factories lie in ruin, the land is exhausted. Lusanga remains a town with no tap water, electricity, or shops. The DRC today imports large amounts of palm oil. Congolese artist Sammy Baloji addresses the long shadow of extractive colonialism in his film Aequare: The Future That Never Was (2023), blending Belgian newsreels from the 1940s and 1950s with present-day footage. The film depicts the National Institute for Agronomic Study of the Belgian Congo, established in 1933 in Yangambi, which sought to “tame and civilise the land, along with its people,” while framing their colonial endeavours as humanitarian service. Their overcultivation inevitably led to depletion. While the land bears witness, it also holds the ability to heal and grow back, lush and inhabited.

In 2017, CATPC had their first institutional solo exhibition at the prestigious SculptureCenter in New York. Later that year, CATPC and HA inaugurated the White Cube Museum—literally a white cube designed by the world-renowned OMA—on former Unilever plantation land as another significant act of reparation. The symbolic white cube is indebted to the plantations, having benefited from this murderous system of extraction, and should thus return to the lands that financed it. It brings capital, visibility, and critical legitimacy to Lusanga. At a conference at SculptureCenter on the occasion of the exhibition, Martens stressed the importance of building a validation and legitimisation mechanism away from the centres of empire to ensure that art is not monopolised by those who have access to those centres. There are too many barriers for artists who don’t have the right passports and don’t come from the right backgrounds and don’t have the right means and didn’t attend the right universities. Only one CATPC member, Matthieu Kasiama, could attend that conference due to these barriers.

There is knowledge to be shared from those who work in plantations, mines, and sweatshops around the world—the locales that finance empire. According to Martens, if art wants to deal with the world in its entirety, it cannot be geographically confined to where profits accumulate. The White Cube is part of the Lusanga International Research Center for Art and Economic Inequality (LIRCAEI), an initiative by HA and CATPC to redefine the mandate of art amid ecological and economic urgencies. “By colliding these two opposite poles of global value chains with each other, LIRCAEI aims to overcome both the monoculture of the plantation system—that exhausts people and the environment and the sterility of the White Cube—a free haven for critique, love, and singularity, that, more often than not, reaffirms class divides.”5

Many prominent Western museums have pledged to decolonise their narratives, collections, and programmes in recent years, but how inclusive can they be if until today no reparations have been paid to the plantation workers who funded them? And if large parts of their collections comprise looted objects? Numerous institutions, such as the Tate Modern in London, the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, or Lady Lever Art Gallery in Liverpool, to name a few, have direct ties to colonial plantations. Repatriating the White Cube to Lusanga means transposing its material impact. CATPC collapses divisions and distances, enabling artists to access global circuits while telling their own stories.

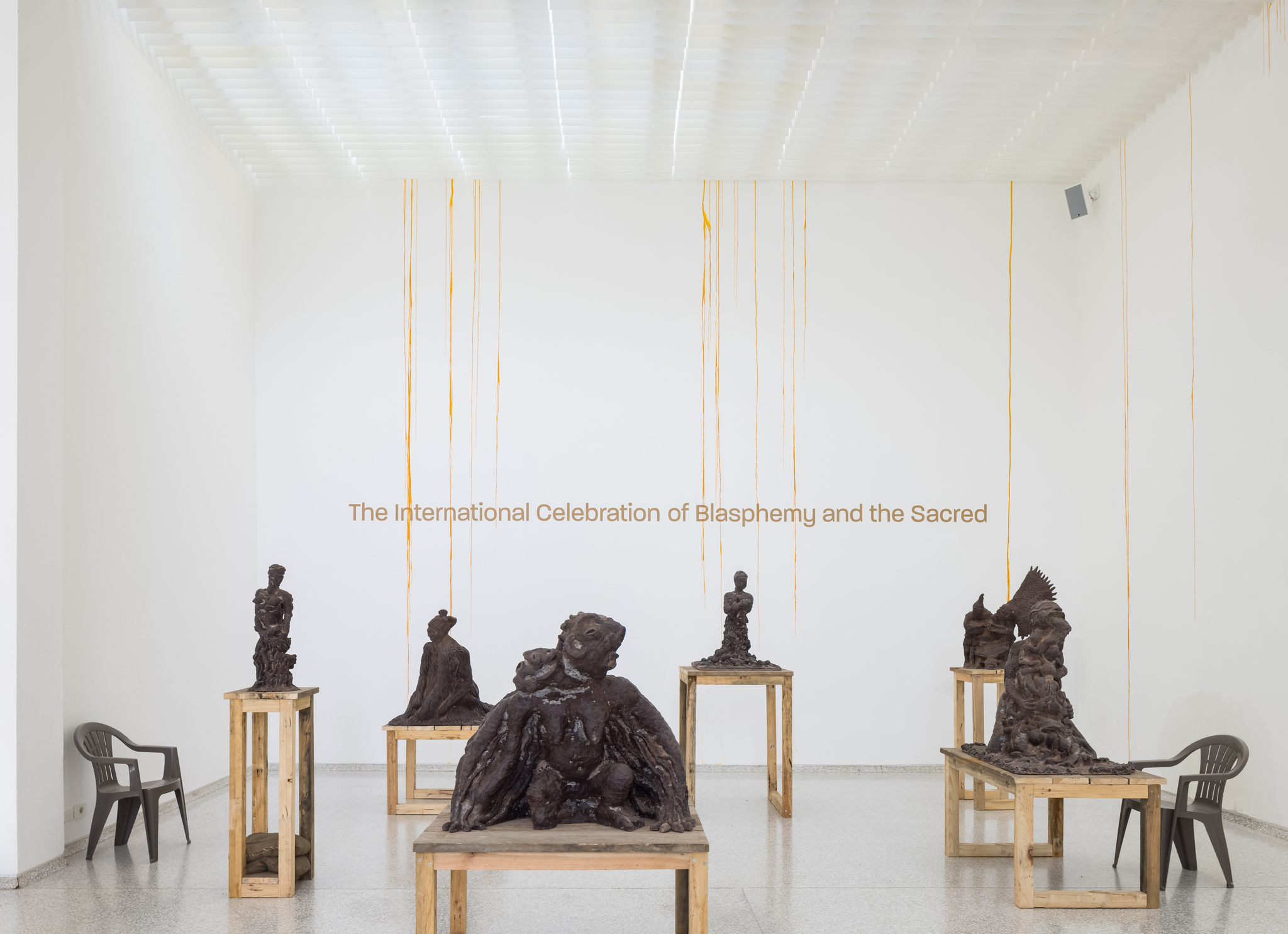

CATPC members work primarily in sculpture, alongside jute tapestries, drawings, films, and performances. At the Dutch Pavilion of the 60th Venice Biennale (Foreigners Everywhere, 2024), they presented The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred, in collaboration with Martens and curated by Hicham Khalidi.6 The title was written in large letters on the wall, palm oil dripping from the ceiling like blood. Cocoa and palm oil sculptures on wooden table pedestals exuded strong odours. The powerful and expressive figures are vessels that transmit colonial histories of violence and denounce capitalist greed, including within the art world, while embodying transformation and repair. Works are created by CATPC members and critiqued collectively. Whether a sculpture is aesthetically and conceptually strong enough to be exhibited is a group decision. Three new films integrated the exhibition: The Judgement of the White Cube; CATPC; and The Return of Balot. A live stream connected the Dutch Pavilion to its twinning exhibition in Lusanga’s White Cube, so visitors to each could see the other in real time.

Still from White Cube, Renzo Martens, 2020. © Human Activities.

The use of technology for the 3D scanning and printing allows for wider circulation of CATPC’s works, while complexifying and subverting traditional notions of provenance, originality, and value, central to how museums attribute significance to objects. In 2022, after the VMFA repeatedly declined to loan the Balot sculpture, CATPC minted NFTs (non-fungible tokens) of it, to the museum’s dismay, and reclaimed its powers through a “digital restitution.” In 2024, the VMFA finally agreed to loan the original to the White Cube for the duration of the Venice Biennale. The live stream in Venice showed the sculpture installed in Lusanga, before it travelled to the Van Abbemuseum for a major CATPC exhibition.

Matthieu Kasiama and Ced’art Tamasala, two founding members and often the collective’s voices, believe art belongs to everyone, without exception. They view their Venice participation as both a reparation of a long-standing injustice and an “unhealthy privilege,” since such an event was never intended for people like them. Still, it is an opportunity to get the message across in representation of the plantation workers in the Congo, and to amplify calls for restitution. The White Cube Museum has linked both locales, and offered Lusanga’s community access to this exclusive event. Art has become a gateway for CATPC to think and act upon material conditions, and address the ills of monoculture, malnutrition, and global warming. To date, they have reclaimed 500 hectares of land, which they are transforming into “sacred forest, which spiritually and practically gives life.” Their mission is to “liberate the plantations in Congo, liberate the land, and also liberate art.”7

By purchasing and regenerating former plantations, CATPC enacts a reversal of colonial land grabs and models a post-extractive, agroecological future rooted in communal knowledge systems. Alarmingly, contemporary palm oil projects in the DRC still echo the same colonial logic CATPC seeks to overturn. In Kwilu province, for instance, the PAPAKIN initiative (2012–2021)—backed by international donors and implemented by state and corporate actors—has led to the displacement of smallholder agriculture in favour of industrial palm monocultures of modified seedlings. Local farmers are often pressured into abandoning subsistence farming to grow oil palm, yet they retain no control over the production chain and are left vulnerable to price fluctuations and land insecurity.8 At the same time, companies like Plantations et Huileries du Congo (PHC), Unilever’s successor, are expanding their operations with no regard for community consent, leading to restricted land access, environmental degradation, and reports of surveillance and intimidation. Between 2021 and 2024, PHC increased its palm oil production by approximately 20% annually, reaching 90,000 tonnes in 2023. The company aims to further expand its capacity to 100,000 tonnes by 2026 and has set an ambitious target of producing two million tonnes by 2032.9These recent dynamics make CATPC’s efforts all the more urgent: a grassroots intervention in a political landscape where land and autonomy are still being wrested from local hands.

CATPC. Installation View of 'The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred', Renzo Martens & Hicham Khalidi for Venice Biennale 2024, commissioned by Mondriaan Fund. Photo: Peter Tijhuis.

For their exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, CATPC has unearthed the museum’s ties to colonial plantations in Indonesia. Henri Van Abbe, founder of the museum, built his wealth by growing tobacco in Sumatra, Indonesia—a country whose agriculture in recent decades has similarly suffered under fraught programmes that sell expensive GMO seedlings to farmers, ruining the people and the land. Upon receiving the museum’s invitation, CATPC decided to visit the plantations in Deli, Sumatra, and meet the people who live and work there. Theirs and their ancestors’ labour had built the museum, so they asked these communities for their permission and blessing before accepting its invitation. Acknowledging the people, the labour, the land, and Indigenous knowledges are first steps to heal from coloniality. CATPC names further crucial steps, such as actively involving the communities in the museums’ lives, visions, and futures. “It's about telling stories with each other,” says Tamasala, “rather than to each other. This is how we consolidate the network of solidarity.” Such dialogues can contribute to envisioning a fairer, more inclusive (art) world, enabling future generations to live in greater harmony.

Marten’s role as facilitator, co-founder, and now collaborator of CATPC has been debated. Without him, there would be no White Cube, early funding, or access to the global circuit of contemporary art.10However, CATPC has acquired its autonomy and operates independently. Tamasala describes Marten as a bridge and partner with whom there is an exchange. Land purchases remain complex, as colonial legal frameworks make it easier for HA to acquire and transfer property to CATPC for their agroforestry and renewable-energy initiatives. Martens argues that complete “autonomy” is unrealistic, since nothing is independent of anything else, and the West is entirely dependent on the non-West. CATPC wouldn’t have shown at the Dutch Pavilion without Martens, but the team ensured that the main voice remained that of the collective.

CATPC sadly lost an esteemed elder shortly after the Venice Biennale opening. Blaise Mandefu Ayawo (1968–2024) was a healer and a sculptor who spent the last decade of his life restoring ancestral lands. His was the centre piece at the Duch Pavilion, titled Mvuyu Libérateur (2023)—the liberating bird, which intervenes when other creatures are in pain or distress, to help them to freedom.11Such is the dream, the wish, the desire, the prayer of CATPC. Their experimental, community-owned cocoa and palm oil gardens provide food and medicine for all. The post-plantation forest is inclusive and multi-species. Sacred art gives rise to sacred forests and vice versa, as CATPC members reestablish severed connections to their cultural heritage through their practices.

The cooperative is a world-building project that rethinks the relationships between art, economy, ecology, and territory. For Tamasala, “each sculpture carries the seed that will bring back the sacred forest.” This is not a metaphorical decolonisation, but an infrastructural one—a demand for reparative justice rooted in ecological, social, and cultural sovereignty. CATPC’s practice challenges art institutions to confront the real economies behind their existence and rethink what restitution can be, as well as what art can be. They insist on accountability: from museums and collectors who have benefited from slavery, and from contemporary cultural actors who continue to benefit from neocolonial structures, even when claiming to decolonise. The plantation is not past—it persists manifold. CATPC’s art is a sincere and powerful summons to dismantle dehumanising structures and to build new commons.

CATPC, Karikacha, installation view Two Sides of the Same Coin, Van Abbemuseum, 2024. Photo: Nick Bookelaar.

CATPC. Installation View of 'The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred', Renzo Martens & Hicham Khalidi for Venice Biennale 2024, commissioned by Mondriaan Fund. Photo: Peter Tijhuis.

Cover Image

CATPC members (from left): Olele Mulela Mabamba, Huguette Kilembi, Mbuku Kimpala Jeremie Mabiala, Jean Kawata, Irene Kanga, Ced'art Tamasala and Mattieu Kasiama. Still from White Cube, Renzo Martens, 2020. © Human Activities

- Mbembe, Achille. 2003. Necropolitics. Translated by Meintjes, Libby. Public Culture 15, no. 1: 11–40.

- Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics. Duke University Press, 2020.

- Unilever website (https://www.unilever.com/our-company/our-history-and-archives/1900-1950/).

- CATPC website (https://catpc.org/home/).

- Renzo Martens website (https://renzomartens.com/repatriation-of-the-white-cube/).

- White Cube website (https://whitecube.online/home/program/catpc-and-renzo-martens-dutch-entry-venice-biennale/).

- "The Congolese Collective CATPC on Representing The Netherlands at the 60th Venice Biennale," ArtReview, 10 April 2024 (https://artreview.com/the-congolese-collective-catpc-on-representing-the-netherlands-at-the-60th-venice-biennale/).

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Turning peasant lands once more into oil palm monocultures," World Rainforest Movement Bulletin 237, 29 April 2018 (https://www.wrm.org.uy/bulletin-articles/democratic-republic-of-congo-turning-peasant-lands-once-more-into-oil-palm-monocultures).

- Francesco De Augustinis and Jonas Kiriko, "DRC’s plans to dramatically increase palm oil production," One Earth, 22 April 2025 (https://www.one-earth.it/en/drcs-plans-to-dramatically-increase-palm-oil-production/).

- Alice Gregory, "Can an Artists' Collective in Africa Repair a Colonial Legacy?", New Yorker, 18 July 2022 (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/07/25/can-an-artists-collective-in-africa-repair-a-colonial-legacy).

- Azu Nwagbogu, "Blaise Mandefu Ayawo (1968–2024)," Artforum, 23 July 2023 (https://www.artforum.com/columns/blaise-mandefu-ayawo-1968-2024-556916/)