Throughout history, the sea and its islands have been considered as vast plateaus of possibility—spaces where one could begin anew, where the burdens of social obligations, legislations, and taxation might be suspended, allowing alternative forms of social life and politics to surface. Anchored in the desire to break free from the shore’s constraints, this fantasy of freedom has animated different myths and tales across cultures, and has also accompanied capitalism since its emergence. The notion of the sea as a realm of freedom resonates not only in cultural imagination but also in legal doctrine, as the high seas (also referred to as international waters) are areas of the world's oceans and seas that are not subject to the sovereignty of any nation—they typically begin 12 nautical miles from the shoreline, beyond the territorial sea.

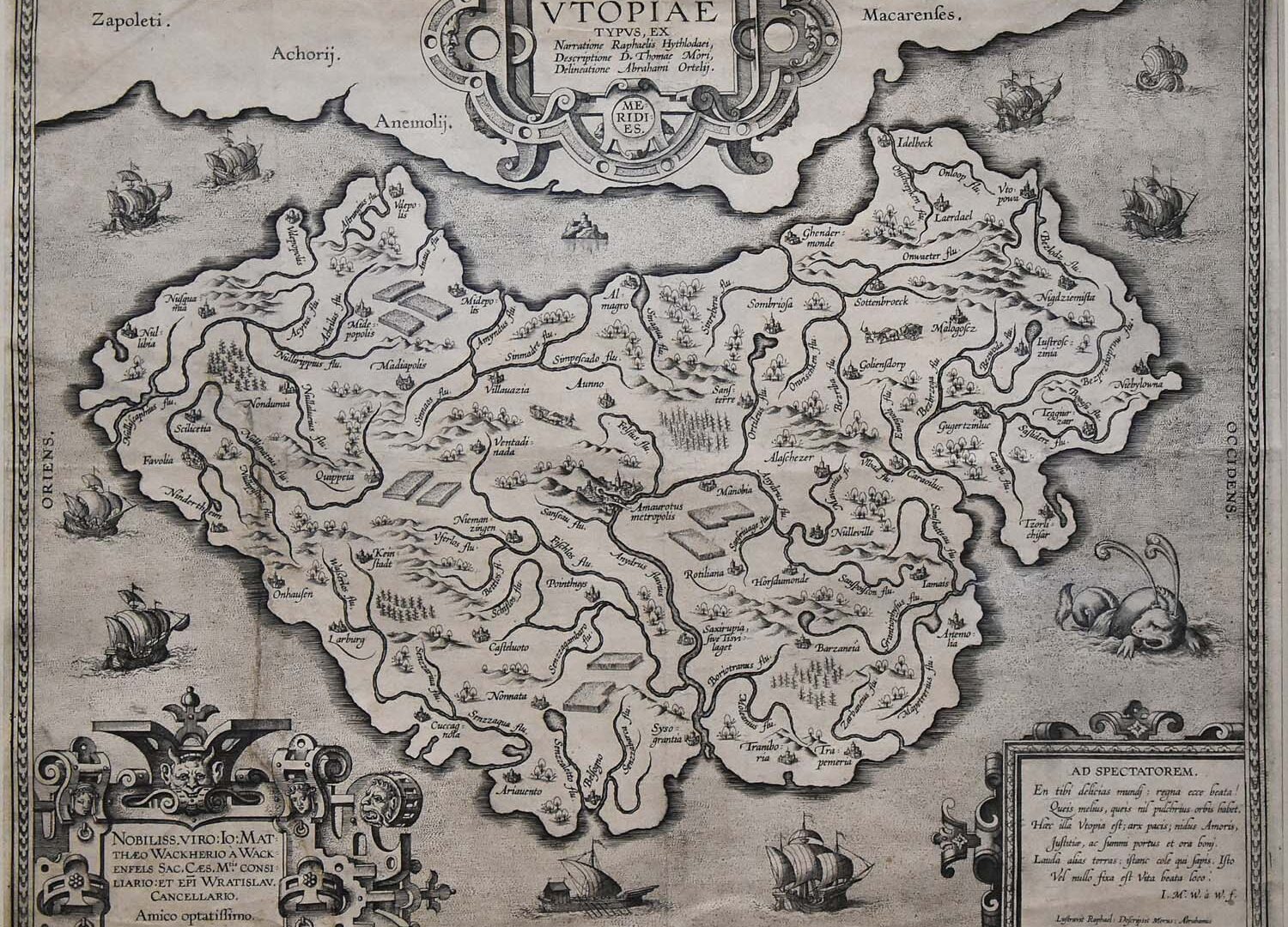

While the vastness of the ocean has been associated with boundless liberty, the island has long been the archetypal place onto which humanity has projected visions of a different world. In Utopia (1516), Thomas More established insularity as the primary geography of hope, coining the very same term that would be used to define visions of alternative flourishing futures, but also their inverse (dystopias). Overall, the spatial, legal, and imaginative conditions of the sea and its islands enable the creation of states of exception—extraterritorial zones where utopian thought and its dystopian shadow can both take form.

If I had to choose one contemporary object that most vividly condenses the libertarian, utopian, mostly masculine fantasies enabled by the sea and its islands, while encapsulating the obscene disparities in wealth, mobility, and carbon impact, that would be the superyacht. More than a symbol of excess and social stratification, the superyacht embodies a deeper imaginary wherein the ocean and its islands have long been understood as a space of separation and exemption; a threshold beyond the reach of terrestrial order, authority, and class; an escape from life and politics on land. In what follows, I argue that superyachts inherit and materialise these seaborne myths, embodying the promises of freedom and sovereignty, separation and connection, exemption and exception, and utopia and dystopia alike. At once grotesque products of neoliberal accumulation and emblems of inequality, superyachts seem to encapsulate the ethos of a global elite that, detached from territorial belonging and disproportionately responsible for the planetary crises, pursues salvation through exclusive forms of isolation and self-sufficiency rather than through collective solutions, thereby revealing how the utopia of the few unfolds as the dystopia of the many.

1. The Sea as a Stage: Continuities in Capitalist Onshore and Offshore Dynamics

Frans Huys, Armed Four-Master Putting Out to Sea from The Sailing Vessels

In Capitalism and the Sea: The Maritime Factor in the Making of the Modern World (2021), Liam Campling and Alejandro Colás offer a comprehensive account of how our economic system is primarily a maritime phenomenon, or, in their words, “a terraqueous predicament.” As many other historians have argued, the Atlantic Ocean was a key engine in the rise of modern capitalism, as this vast maritime domain served as the stage for one of the most brutal commercial systems ever devised: the triangular trade, which linked Africa, the Americas, and Europe in a circuit of exploitation and death which enabled the so-called “primitive accumulation” that fuelled the emergence of capitalism. According to Campling and Colás, while the sea played a central role in this process of colonial expansion and accumulation, it continues to sustain capitalism: global trade, supply chains, undersea internet cables, and new possibilities of resource extraction all consistently depend on maritime networks. In this sense, it could be argued that the future of capitalism is strictly tied to the sea—its last frontier,1 as some scholars have described it—because, unlike terrestrial space, where nearly all land is claimed by states, vast stretches of the ocean and their resources remain a global “common,” a rarity in a largely privatised and commodified world.

In this long historical relationship between capitalism and the Atlantic Ocean, Campling and Colás identify a persistent continuity: the interplay and tension between onshore and offshore, land and sea—a defining dynamic that not only shaped capitalism’s early development but continues to structure its present operations. Inherited from mercantilism, this divide conceives of the onshore as the regulated domain of domestic markets, where imported goods are sold at high prices, while the offshore is the space where resources are extracted cheaply, traded freely, or violently seized. Yet the offshore has always signified more than material exploitation: it is a realm of exemption and exception, a legal and political “elsewhere” where ordinary rules, customs, and ethics that govern life on land are temporarily suspended.

The Atlantic islands and their colonies epitomised this divide with cynical brutality. Their strategic isolation, enabled by the surrounding waters and vast natural resources, made them both sites of extraction for imperial powers, as well as laboratories where they exploitative practices unimaginable on land could be applied. The onshore–offshore duality enabled by the sea thus not only defined colonialism and early capitalism but continues to underpin the global economy today, as many of these same islands still serve the dynamics of offshoring in new forms.

With neoliberalism's ascendancy in the 1980s, the dismantling of national barriers to trade and the deregulation of financial systems rendered capital ever more fluid, circulating instantaneously across borders through newly discovered digital technologies and escaping regulation through complex offshore architectures. While offshoring has proliferated since the 1980s in different domains (labour, waste disposal, legislation, etc.), tax havens are perhaps the most crucial manifestation of this practice. These are offshore financial centres offering financial secrecy, minimal taxation, and flexible legal frameworks to companies and private clients. They host shell companies, insurance schemes, flags of convenience, datacentres, and opaque trusts that conceal ownership and wealth.

Today, nearly 83% of major European corporations maintain offshore subsidiaries; more than half of global trade passes through such jurisdictions; nearly all high-net-worth individuals hold offshore accounts for tax avoidance; and 99 of Europe’s largest companies rely on offshore structures. As a result, between one quarter and one third of global wealth now floats beyond the reach of national oversight—adrift in the offshore2. Offshoring thus perpetuates a geography of inequality, enabling the super-rich to evade taxation, accountability, and redistribution. It consolidates privilege while eroding the fiscal and social foundations of the onshore world. What was once a colonial relation between centre and periphery now takes the form of a systemic imbalance between those who can accumulate and move capital freely—corporations and the ultra-rich—and those who cannot.

In Offshoring (2014), John Urry points to the sea as a key contemporary facilitator of tax avoidance. As he notes with a slight sense of humour, “successful tax havens operate with low taxes, wealth management, deregulation, secrecy and often nice beaches.” Around 60% of the world’s tax havens are located on islands, with only a few exceptions outside coastal states. In the Atlantic alone, of the 28 jurisdictions commonly recognised as tax havens, 24 are islands, and every one of them was once a colony or an overseas dependency of a European empire. These islands, once peripheral outposts of mercantilist and colonial expansion, now inherit and update, in financial terms, that same divide between the onshore and the offshore.

Campling and Colás explain this persistence via both material and symbolic factors. Materially, small island developing states (SIDS) possess few export options beyond tourism and fishing, and offshore banking enables them to commodify their very jurisdictions, effectively selling legal sovereignty as an economic asset by tailoring banking and tax laws to the preferences of their wealthy onshore clients3. Symbolically, the ocean and its islands, as seen before, have long served as canvases for utopian and libertarian projection, as they allow for the creation of different spaces of exception. From colonial outposts to fiscal paradises, to spaces of luxury and futurism like Dubai’s artificial archipelagos, to sites of imprisonment like Guantánamo, and to private insular enclaves where sexual fantasies where enacted (like Epstein’s island), insularity has continuously enabled suffering, privilege, and impunity. These spaces reveal how isolation underwrites the coexistence of utopia and dystopia, and how seclusion becomes a condition for freedom, domination, and escape.

Within this genealogy of maritime exception, the superyacht can be understood as both a product and performance of the offshore condition—a contemporary embodiment of the libertarian and utopian fantasies historically projected onto the sea. Functioning as a mobile island, it materialises the sovereignty of insularity, the liquidity of capital and lifestyle, and the opacity that defines both the sea and offshore worlds. It gives partial form to a centuries-old dream of autonomy from terrestrial order: the aspiration to inhabit a self-sufficient realm liberated from law, taxation, and collective responsibility. In this sense, the superyacht revives the maritime imaginary of freedom associated with nautical empires, pirates, and utopian islands, while rearticulating it in the key of neoliberal individualism and consumerism against the backdrop of planetary collapse.

2. Superyachts and the Offshore Elite: Freedom, Privilege, and Escape

Azzam, the world’s largest superyacht (180 metres)

As the term implies, to qualify as a superyacht, size is the decisive factor. A conventional yacht becomes “super” at 30 metres, though many reach extreme lengths (Salle, 2024). It is the case of the Azzam, a staggering 180-metre vessel owned by the Emirati prince. Buying an “average” vessel costs around 30 million euros, while the most extravagant models can reach up to 600 million euros. The purchase price for owning these floating palaces is only an initial investment, as maintaining one demands staggering resources. A 70-metre boat can consume up to 700 litres of fuel per hour (about 1,000 euros), and more than double that at full speed. Needless to say, chartering one for a week can reach astronomical costs and carry a carbon footprint equivalent to several years of an average person’s life on land4.

Within these floating palaces, luxury takes absurd forms. Inside the lengths of Azzam, for instance, one finds a gym, a cinema, two swimming pools, a golf training room and two helipads. Another vessel, Al Said, stretching 155 metres, contains a concert hall large enough for a 50-piece orchestra. The comparatively “modest” Serene (a mere 134 metres) includes a room where snow machines generate four inches of snow on command. While the incredible dimensions of these vessels can accommodate different ambiences and extravagances, maritime regulations limit the number of guests permitted on board to just 12, regardless of the size of the boat5. Crew numbers, however, are unlimited, provided they have completed the required sea survival training. This regulatory distinction makes the spectacle of these boats even more striking: palatial vessels costing hundreds of millions ultimately serve no more than a dozen guests—an exclusivity that starkly underscores the opulence of wealth, the inequalities of the global economy, and the environmental cost that follows.

As the previous overtly anecdotal paragraphs suggest, owning a superyacht is a privilege restricted to only a microscopic fraction of humanity: the super-rich. While they may differ in nationality, industry, or politics, what unites them beyond their enormous wealth is gender. This competition for size, power, and prestige is entirely a male affair. Among the forty largest private superyachts, an astonishing 87.5% are owned by individual men; not a single one belongs to an individual woman; the remaining 12.5% belong to states, royal families, or corporations. In other words, the superyacht remains the ultimate floating boys’ toy, a monument to masculinity inflated to nautical proportions, with royals and billionaires at the helm.

However, the superyacht, when viewed closely, is not only an object of luxury for a microscopic fraction of humanity: it also mirrors the very structures and contradictions of contemporary capitalism. It is both a product and a symptom of the onshore–offshore dynamics that, as Campling and Colás remind us, have shaped capitalism since its origins. At once a mobile island, a floating tax haven, and an enclave of exemption in motion, a safe place to store wealth, it condenses into a single architecture the rise of inequality, the acceleration of ecological collapse, and the persistence of spatial and legal segregation. The superyacht embodies the logic of a transnational elite whose mobility depends on the immobility and dispossession of others.

If regarded as a mobile island, it revives and distorts the old idea of a “space of possibility” into a floating architecture of exclusion and exemption, where freedom is privatised and sustained through extreme inequality and exploitation. Both the island and the yacht embody fantasies of autonomy and exemption as sovereign microcosms adrift from the obligations of the collective life onshore. The superyacht enables the libertarian conviction that freedom can be attained through withdrawal rather than relation, through evasion rather than accountability. It realises a spatial fantasy of sovereignty detached from territory—a self-contained microstate supported by private infrastructure, able to navigate jurisdictions and climates at will.

As a floating tax haven, it both results from and reproduces the offshore economy, operating through the same legal fictions that sustain it. Most superyachts are registered under flags of convenience issued by the same islands that anchor the offshore economy. Through these registrations, owners can drastically lower the costs of buying, maintaining, and operating these vessels by channelling their financial transactions through layers of offshore companies, and as such benefit from the deregulated labour regimes typical of these territories, where employment protections are minimal and precarity is normalised. Many even reside aboard for more than three months to claim non-resident tax status from their countries, extending their exemption beyond the sea. In this sense, the superyacht does not merely symbolise the offshore—it enacts it, performing concealment, deregulation, and evasion as forms of life.

If framed as enclaves of exception, superyachts embody not merely wealth in motion but almost unbounded sovereignty. They occupy a peculiar legal and political threshold that is exempt from the ordinary constraints of territory, taxation, and labour law, and yet depends on the infrastructures and jurisdictions they evade. Onshore, the owners are subject to national legislation and public scrutiny; offshore, in international waters, they slip into a state of exception where rules dissolve into evasion. Here, the sea becomes not a void but a pliable legal medium that allows the powerful to tailor their exposure to authority.

As investigative journalists and economists have noted, superyachts are also “ideal vehicles for concealing and protecting wealth”6. The recent seizures of vessels owned by Russian oligarchs have made this visible, as their floating assets suddenly became hostages of geopolitics. For example, the Amadea—a 106-metre yacht linked to Suleiman Kerimov, registered in the Cayman Islands and owned through a local shell company—was seized in Fiji, and many others around the world suffered similar fates. Such cases reveal how also oligarchic wealth circulates through a web of flags of convenience and offshore registrations, exploiting the geography and legislation of the sea to evade taxation and accountability.

Superyachts encapsulate not only the liquidity and opacity of capital but also the lifestyle of the global elite. As early as 1967, in Everyday Life in the Modern World, Henri Lefebvre observed that “the Olympians of the new bourgeois aristocracy no longer inhabit. They go from hotel to grand hotel, or from castle to castle, command a fleet or a country from a yacht. They are everywhere and nowhere”7. His remark remains strikingly relevant today: the hyper-mobility of the super-rich allows them to move beyond the legal, social, and economic constraints that govern the lives of ordinary people. The super-rich embody a luxurious dystopian version of Zygmunt Bauman’s condition of liquid modernity, representing a social order in which stability is devalued and power resides in the capacity to remain in motion, to slip through the solid structures of affection, regulation, taxation, and accountability. Superyachts materialise this liquidity: sovereignty without anchorage, belonging without attachment.

As Rowland Atkinson and Sarah Blandy note in A Picture of the Floating World: Grounding the Secessionary Affluence of the Residential Cruise Liner (2009), this capacity to mobilise both capital and oneself at will has produced a supranational class largely beyond regulation—a “kinetic elite” navigating a transnational archipelago of superyachts, private islands, luxury compounds, and exclusive enclaves, crafting a lifestyle predicated on movement and detachment. This hypermobility destabilises conventional notions of nationality and sovereignty. As Emma Spence argues in Beyond the City: Exploring the Maritime Geographies of the Super-rich (2017), the capacity to obscure wealth, status, and identity through the continuous movement of assets and bodies between jurisdictions compels us to reconsider what nationality and accountability mean for the contemporary elite.

Yet, beneath their performative autonomy and mobility lies a system marked by a rigid hierarchy, as the architecture and operation of superyachts reproduce the same structures of inequality and social stratification that sustain life on land. Crew and guests inhabit strictly segregated zones: private suites, pools, and entertainment areas for owners; invisible service corridors and tiny quarters for staff. Only a few crew members interact with guests; most remain unseen, maintaining the vessel’s perfection from below deck—as brilliantly depicted in Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness. Employment on these boats also mirrors global precarity, as few crew members are directly employed by owners: typically, only the captain holds a long-term contract; the others work short-term, freelance, often without benefits.

At the same time, superyachts are products of structural inequalities and a stark division of wealth. They exemplify how a tiny minority lives a vastly different economic and social reality from the rest of the world. According to Oxfam, in 2023, the richest 1% of the world’s population seized nearly 63 % of the wealth created between 2019 and 2021. In this context, it is impossible not to view superyachts as physical manifestations of that inequality. These floating utopias, where exemption and privilege grant freedoms denied to most, drift through a world of mobility, isolation, and exemption, while the rest of humanity remains anchored to a terrestrial, regulated, and increasingly precarious world threatened by ecological and social collapse.

3. Titanic Ambitions and Fantasies of Escape: Floating Utopias for the Few and Sinking Dystopias for the Many

the submersible that imploded in June 2023, killing five people. Photograph: American Photo Archive/Alamy/PA

As with all utopias, superyachts are both projection and paradox: the dream of perfection for a few, built upon the exclusion of many. Like islands, they embody the contradiction at the heart of utopian thought: the promise of freedom that depends on separation, privilege, and dispossession. This tension was already inscribed in the very text that coined the word "utopia." In Thomas More’s book, we find the Portuguese sailor Raphael Hythloday denouncing European greed and inequality while recounting the discovery of an island (Utopia) where property is shared and oppression abolished. However, the the story Utopia hides a darker origin: before being an island it was connected to the mainland by an isthmus until its king, after dispossessing the local population, ordered it cut off from the continent by forced labour. The birth of every utopia seems to be inevitably connected to exclusion and violence8.

The superyacht, as a floating island, embodies the same paradox. It is at once the libertarian fantasy of the ruling elite—mobile, sovereign, and exempt—and a dystopian mirror of the inequalities that define our age. On its decks, one can glimpse the full architecture of contemporary life: the division of labour, spatial stratification, and the escape of the powerful from finding solutions for the majority of the planet. Media theorist Douglas Rushkoff argues that, since the 1980s, the ultra-rich have abandoned any pretence of collective survival in favour of what he calls the "insular equation"—the belief that “the winners will be the ones who manage to escape”9. Superyachts are the latest materialisation of this fantasy of exemption: extraterritorial zones where the rich rehearse survival in luxury while the world around them struggles to stay afloat.

Especially considering the current ecological crises, we can see how superyachts encapsulate a desire not only for freedom through the sea but also for escape, as they symbolise both the denial of climate change and the option to withdraw from responsibility. This fantasy of escape is not new. As early as 1919, Nikolai Bukharin described the bourgeois impulse in times of crisis as driven by the fear of impending social catastrophe10. Nowadays, the strategies of escape seem to be multiplying. Whether in orbit, as in SpaceX’s Mars colonies, or in international waters, as the floating communities of The Seasteading Institute—private, extraterritorial communities beyond the reach of nation-states—all these projects share the same desire: to plant flags, flee the consequences of the system they helped create, and start anew.

If a massive boat like the Titanic has long served as a metaphor for the arrogance of the ruling class in its swift passage from self-confidence to self-destruction, its 2023 spin-off, the Titan, offers an even more accurate and poignant image. During a private expedition to the wreck of the Titanic in the North Atlantic, a group of ultra-wealthy passengers embarked on a 250,000-dollar venture in a submersible of dubious engineering, driven by an Xbox controller and operating beyond any regulatory oversight. As the vessel reached a certain pressure, it imploded, causing the death of everyone on board. The story of the Titan shares the same mixture of detachment and hubris (the ancient sin of those who defy limits, an arrogance against the gods) that animates the broader culture of elite escapism, from outer space to the ocean floor. In Greek mythology, the Titans were cast out of Olympus for their hubris. The Titanic was proclaimed "unsinkable,"11 while the Titan’s creator claimed his submarine could explore the deepest depths “safely without breaking the rules.”12 Both the enormous cruise ship and the tiny submarine, as their names suggest, were propelled by hubris and perished because of it.

While no one survived aboard the Titan, the sinking of the Titanic tells a slighly different story—one of escape and class. As the ship descended into the Atlantic, wealth and privilege dictated the terms of rescue: the captain and the wealthiest passengers seizedthe few available lifeboats and gave the band instructions to keep playing cheerful music on deck in a desperate effort to normalize the situation.This scene embodies a recurring logic in moments of crisis: a sharpseparation between safe spacesreserved for the privileged minority and zones of exposure where the others are left to confront the imminent threats as if everything is under control.The very same hubris that doomed the submarine and the cruise ship, along with the persistent myth of the sea as a realm of separation, seems to reappear today in the culture of superyachts and of the global elite.These colossal boats sustain the old maritime fantasy of liberation and escape, yet theirdesignsand functioning reveal the very contradictions that define our age: legal and economic inequality, spatial segregation, and ecological catastrophe. They also disclose the mindset of a ruling class that has already normalised the prospect of climate breakdown and arrogantly assumesitcan outrun its consequences. Sheltered within their superyachts or isolated enclaves, contemporary elites continue to elaborate luxurious strategies of withdrawal as the world edges toward critical thresholds. Still driven by hubris and sustained by immense concentrations of wealth and an utopian faith in progress, they continue to steer the planet toward dystopian horizons, as they demand that the band play joyful melodies amid the imminent wreckage.

Cover Image

Engraving by Ambrosius Holbein for the 1516 edition of Thomas More's Utopia

Proofreading

Diogo Montenegro

- Guy Standing, The Blue Commons: Rescuing the Economy of the Sea (2021)

- Urry, Jonathan. Offshoring. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014

- Campling, Liam, and Alejandro Colás. Capitalism and the Sea: The Maritime Factor in the Making of the Modern World. London & New York: Verso, 2021.

- Salle, Grégory. Superyachts: Luxury, Tranquility and Ecocide. Cambridge & Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2024.

- Khalili, Laleh. “Showing Off: Superyachts.” London Review of Books, 9 May 2024. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n09/laleh-khalili/showing-off

- Zucman, Gabriel. The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Lefebvre, Henri. Everyday Life in the Modern World. London: Allen Lane / Penguin, 1967, 94

- Campling, Liam, and Alejandro Colás. “Haven and Hell.” In Haven, by James Newitt. Lisbon: Galerias Municipais de Lisboa, 2023.

- Rushkoff, Douglas. Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires. Melbourne: Scribe Publications, 2022.

- Bukharin, Nikolai. The Economic Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972.

- Petroski, Henry “100 Years After the Titanic, We’re Still Not Unsinkable,” Washington Post, April 6, 2012

- Bella, Timothy. “Titanic Submersible CEO Stockton Rush Said He Was Worried About Vessel Not Surfacing.” Washington Post, June 21, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/06/21/titantic-submersible-ceo-oceangate-stockton-rush/