(SOMETIME BETWEEN THE END OF THE PANDEMIC AND NOW)

Salomé Lamas's work is a deep immersion in the complexities of reality and its manipulation, exploring a fluidity between documentary, fiction, and installation. Her approach favours experimentation and the questioning of narrative conventions, creating a cinema that does not attempt to provide answers but instead leads the spectator to reflect on truth, politics, and the human experience. In this interview, Salomé shares her vision on how projects take shape, the tension between the real and the symbolic, and the role of the filmmaker and artist as agents of reflection in the contemporary world.

Throughout the conversation, she reaffirms that her work is not concerned with merely capturing reality, but with challenging and questioning it in innovative ways. A constant search for areas of friction, an eagerness to explore new languages, and a reflection on the role of art in today's world sit at the centre of her practice.

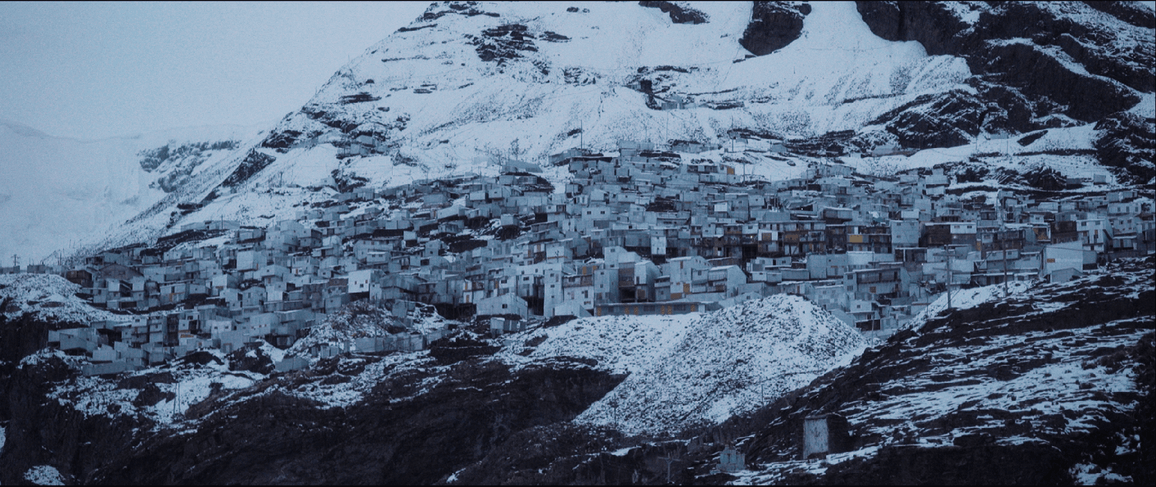

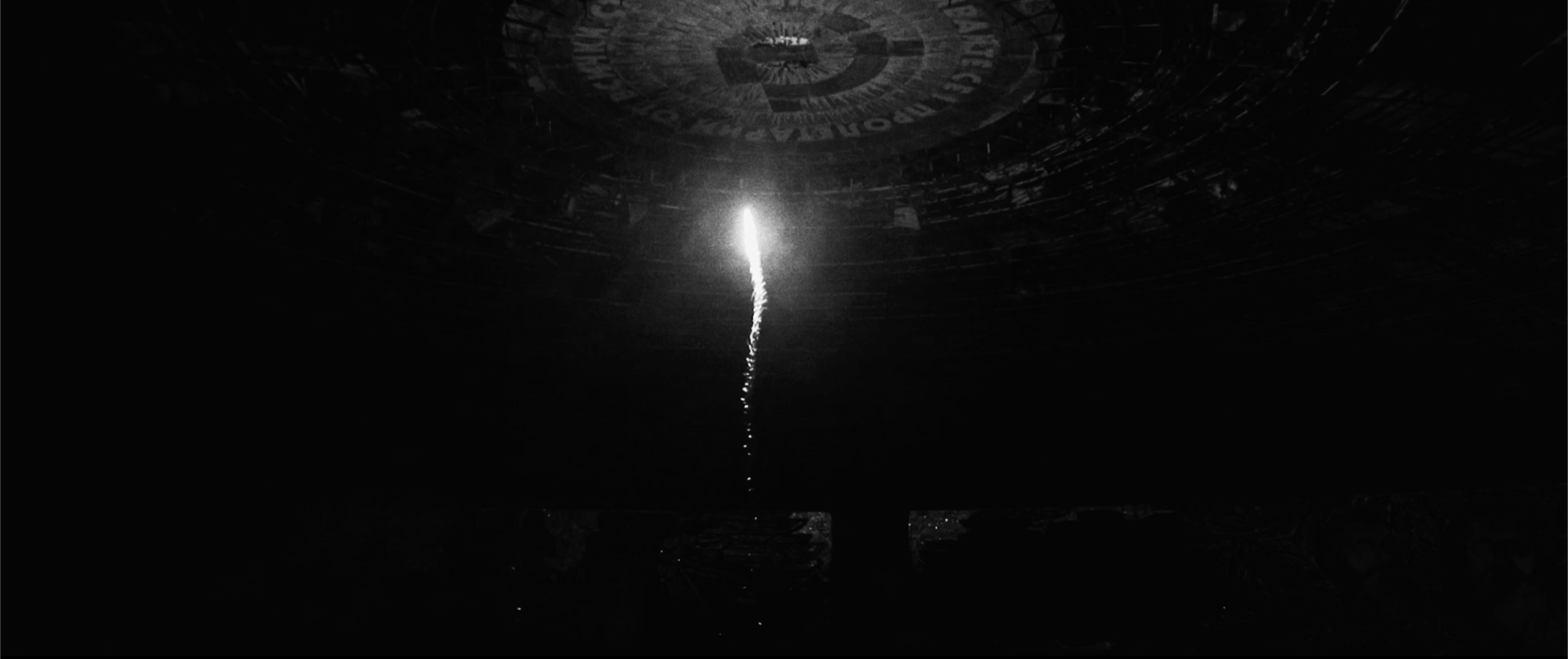

Salomé Lamas, El Dorado XXI, 2015-2016, still. Courtesy of the artist and producers.

Sara Magno: You've produced more than thirty projects, which have been installed and exhibited internationally, in cinema auditoriums as well as in contemporary art galleries and museums. Your work has been contextualised in visual culture, art studies, and film studies, ranging from films to installations and publications. How do you deal with the fluidity of languages and formats?

Salomé Lamas: My background straddles film and the visual arts. I see fluidity as something natural—really, the only coherent path. It’s something quite different from mastering one discipline. Here, each project demands its own specific approach, and material questions arise according to the needs of the work. Projects invariably grow out of questioning—if you prefer, out of wonder or desire. They feed from me, from the world we inhabit, from the mystery of existence. There is something spiritual here that I want to preserve, and which aligns with the sense of coherence that will later inform the ethical principles I follow. It's as if I've lost something that I can't quite identify. I also question the interest of what is being sought and its potential recognition. Above all, I’m a nonconformist who is no stranger to the idea of separation.1

It's essential to acknowledge that the moving image plays a central role on many levels. Artistic work has ways of creating thoughts that are not our own, but with moving images, death is a constant, and that interests me. Manipulating time and temporal order helps shed light on anthropocentric definitions of death, the conscious and unconscious content we project, and the technical conditions that allows us to engage with the metaphysical properties of time.

I was recently taking inventory of work, and the process of recognition is analytical. There are systemic matters that must be observed. Above all, I'm trying to understand the environmental factors that influence the development of projects, particularly in relation to their initial driving force. The practice encompasses various collaborative dimensions, including projects initiated by third parties, but not only those, where the impacts of that intervention are visible—whether in terms of project management, timing, production value, audiences, or distribution. These are delicate balances.

I want to preserve a space of freedom that can serve either as retreat from the turbulence of the world, or a ghetto pushed aside by the market's domination. To choose the margin is to collapse domestic and professional life into uncertainty. I don't advocate for autonomy as a defining characteristic of cultural practices, but rather as a form of resistance to capitalist ideology. I am critical of cultural policies that claim to foster emancipatory and democratic practices, positioning autonomy not as isolation but as a framework for critical engagement with societal structures, while preserving space for artistic freedom and innovation.

The irony is that this autonomy is itself a function of capitalism—controlled, efficient, promoting pre-packaged experiences as marketable cultural products, obedient to established business rules, systems of surveillance, and the legitimisation of methods of domination. This encompasses the entire cycle of cultural production, from artistic creation (including style, composition, and materiality) to technological and institutional mediation (encompassing social organisation and infrastructure). So, when you recognise the fluidity of my approaches, I answer that there is no formula, but rather an unfolding of encounters with the unknown2—a wandering. And that, above all, is what I want to preserve.

However, this sense of freedom does not necessarily translate into independence from broader economic, political, and social forces. Artistic autonomy is not simply a retreat or a space of resistance, but a battleground.3

Returning to your earlier question, materiality is not an end in itself but a function. By this I mean that I value construction over composition. These are ontological problems that unfold across both concrete and abstract planes, where the idea of becoming is the natural essence of materiality.4The ecology of a project is like a tree, with as many variables as the number of branches borne by its crown. If we examine the developmental environment of a project and my role as a manager of human and material resources, we observe that there is no beginning or end, but rather a coexistence of becomings that destabilise established forms and open up space for new potentials of existence.

The most favourable environment for the project's performative development is in the micropolitics of intensities—in multiplicity, rhizomatic non-linearity, and coexistence. While the macrostructure is essential to preserving the project’s essence, my engagement with the microstructure, through its spectrum of possibilities, is dedicated to addressing procedural issues.

This approach is holistic, seeking a balance between two forces—subjective and objective—which are not always compatible, but which I regard as complementary. Subjectivity is the matrix force of the project, animated by the sensible (emotional, spiritual, vitalist), while rational objectivity enables its materialisation across both abstract and concrete domains.

Some projects face greater difficulty in stabilising materialisation and reaching completion than others. This often results from a clash between intentions and environment (production conditions).5 Let’s keep this open, as it connects to other matters. I’m interested in the work as a process of thought—one that invites intersections and multidisciplinarity, where formal deontological structures play a role and the spectator is active. I apologise, but your question touches on different dimensions.

Salomé Lamas, Fatamorgana, 2016-2019. Cortesia da artista, still. Courtesy of the artist and producers.

SM: Each project opens a door onto a different social reality, usually characterised by its geographical and political inaccessibility. You show an interest in impenetrable, politically ambiguous contexts and appear to be guided by concerns and by a need to problematise reality that otherwise would not be possible. The web of relations that constitutes the socio-political fabric of your projects is made visible through representational strategies, for which you have adopted the term parafiction. When did this idea emerge for you, and how do you explore this tension?

SL: I learned from what you helped me understand.6 7

I begin from the principle that we do not have access to a stable reality. Instead, we are confronted with an excess of meanings, interpretations, explanations, manipulations, (de)constructions, and evaluations that feed into narratives and systems that sustain and occupy us. Consequently, the need for appropriating the idea of parafiction arises from questioning how human subjectivity is formed, drawing on psychoanalysis with the aim of clarifying and expanding concepts such as the real (something that is out of reach), reality, symbolic, and imaginary. This is what fundamentally leads me to operate at the border between fiction and non-fiction, employing representation and hypothesis generation through specific meditative criteria and a deontological code relative to plausibility, while consciously assuming the “task of the translator”8—comparable to illusionism—and pushing its boundaries.

In this context, I draw on distinct non-fictional strategies, including ethnographic research, as well as thought experiments, reflexivity, re-enactment, and performativity, among others, to explore the limits of fiction. This is evident in the development of a working methodology where we find various manifestations of parafiction, such as scenarios where characters and fictional stories intersect with the world as we experience it. These combined strategies, to the detriment of other speculative aspects, form a sort of hypothesis that retains a degree of exactitude with reality but simultaneously questions its authority. Through parafiction, it becomes possible to take a convention and deconstruct it, distort it, expose the impossibility of providing evidence for the truth—to the point that doubts are raised about its validity—while still producing reasons to understands it as plausible.

I’m interested in problematising both sides of the boundary between historical and imaginary worlds, and in recording how they have changed over time, by understanding parafiction as a fundamental translation tool for defining identity, language, and culture; by intensifying, exaggerating, and speculating on how the world is made sensible, triggering moments that reveal their fabrication, in a post-truth context intensified by the technological and globalised nature of our time. Revealing this transformation is a continuous, thorough undertaking, but also a spiritual one, capable of relating the individual sphere (private) with the social sphere (public), and thereby introducing new information and perspectives on our past, present, and future. Thus, although conscious of limits and apparent contradictions, parafiction helps give form to the chaos of life and endow it with significance, in a compromise between reality and its fictionalisation.

SM: Over the past few years, I’ve noticed you working in very different ways. It seems that what motivates you isn’t just the challenge and opportunity to explore various languages and formats, but also collaboration and, to use your own words, production ecologies. What motivates you to begin a project, and how do you decide on its themes?

SL: If the unforeseen is where something new emerges, uncertainty is a space where both possibilities and impossibilities coexist. Psychoanalysis teaches us that we are made of paradoxes. On the one hand, I have a need for control and security: a sense of permanence. Yet, in my work, I constantly seek evasion, a lack of control, and transgression: a sense of risk. I am drawn to challenge, and perhaps to inconstancy, though I understand that this, too, is a way of precipitating production. The paradoxes I explore in the work are externalisations of internal inconstancy, as if I must invent a reason that allows me to produce. Because, ultimately, there is nothing to produce—only to remain uncreated in creation, where meaning has drifted away. Let's talk about giving meaning.

It's not an individual project, a production, or an end in itself, but a collection limited by the unbearable pain of the incomplete that I mentioned. There it is—the thing that I believe I have lost and that am forced to look for. The process is invariably solitary, like the human condition. Let's talk about individuals (private) and communities (social). Let's talk about maternity hospitals and orphanages. Let's talk about the dialogues established with the brothers and sisters of what we produce, where I find companionship and anonymity rather than authorship.9 Let's talk about our emotional relation with sensible time (ennui) and our obsession with death—with finitude. To tell a story is, to a certain extent, to postpone the end of the world; but to reinvent the world, paying close attention is enough. Let's talk about death as a privilege. Let’s talk about how certain phenomena find parallels across different scales. What I look for in the work responds to various personal needs—that curiosity about everything that surrounds me. In a way, the projects are the vehicles that allow me to experience and problematise the world in its complexity. There is a physical, mental, and spiritual dimension here—a way of life, a way of being.

The projects arise from personal interests, affections, and encounters—but above all, from concerns. It is precisely these concerns that lead me to explore different scales, social formations, mappings, systems, and gestures as a cartographer of human activity,10 moving away from what is familiar, dominant, or ordinary. I place both myself and the spectator in an unstable space—neither “here nor there,” but elsewhere. And that has drawn me to critical zones, geographies of sacrifice, and controversial themes.

I believe these liminal, silenced, ambiguous territories—geographical, legal, ethical, and marginal— should be discussed in public. I try to identify symptoms in contexts that could erupt at any moment into acts of environmental and human violence. Through the work, we come to understand the transversality of research informed by critical epistemology, transnational and subjective, focusing on the possibilities opened up by ecological thought, as well as the connection between artistic praxis, economics, aesthetic mutations, and contemporary philosophy. Above all, I seek to promote critical dialogues that encourage the public to confront the complexities of human experience and broader social dynamics, centred on migration, post-colonialism (necropolitics), and a critique of capitalism.

If you prefer, the process is intuitive yet deeply rooted in research and personal encounters—both with people and geopolitical contexts. I often begin with images, questions, or a tension that I perceive in the world, in order to explore its contradictions. This resonance might stem from a person with a complex biography, a place marked by history and conflict, or a political-legal structure that appears abstract but has tangible consequences. These are individualities or case studies, yet what I formulate internally are images. Themes emerge in this process, rather than being predetermined. The problem lies in the complexity of these contexts; I am constantly led to question the relationship between narrative, memory, and history, in what appears unrepresentable or the historically invisible. It is here that the work finds its reflexive need, as well as the dialogue between disciplines, viewpoints, and methodologies. This approach is interdisciplinary, and speculative, and involves contact with other specialists. However, it is in the fieldwork that I seek an eclecticism of expressions and modes of sociability which allows me to establish fields of tension. It always falls short, and this is painful for me, especially when it culminates in scenarios of political emergency.

I have an abstract mode of thinking that can, at times, create communication barriers, but also allows me to work through analogies across different scales, to expand and visualise systems. I project an excess of variables in order to establish a grammar. Because of this, at a procedural level, I tend to construct and deconstruct excessively. The initial movement is one of construction, but when I reach a point of saturation, I seek balance by deconstructing everything, at the risk that nothing remains.

SM: How do you balance rigorous research with creative freedom when working on your projects?

SL: I'm obsessive, but I understand that part of the research involves theoretical material—with sociological and philosophical derivations—despite having no formal training or academic framework. I recognise that the projects have been accompanied by a growing body of writing that either finds its own way or remains private, functioning as an unorthodox artistic research methodology. For the materialisation of the project, I prioritise experimentation, improvisation, and risk, as I mentioned, because they trigger intuition and the possibility of action. Otherwise, I wouldn't produce, and would limit myself to study.11This is particularly noticeable in confrontations with real-world settings, in work produced in the field.

I realise that I’m occupied with many of the same concerns as others. I'm thinking of conversations held with agents from other fields where we discuss similar symptoms, where I recognise the different roles at play, and where I often wonder what it would be like for those people to inscribe their bodies in the territory—to feel, to speak nearby, rather than about it.

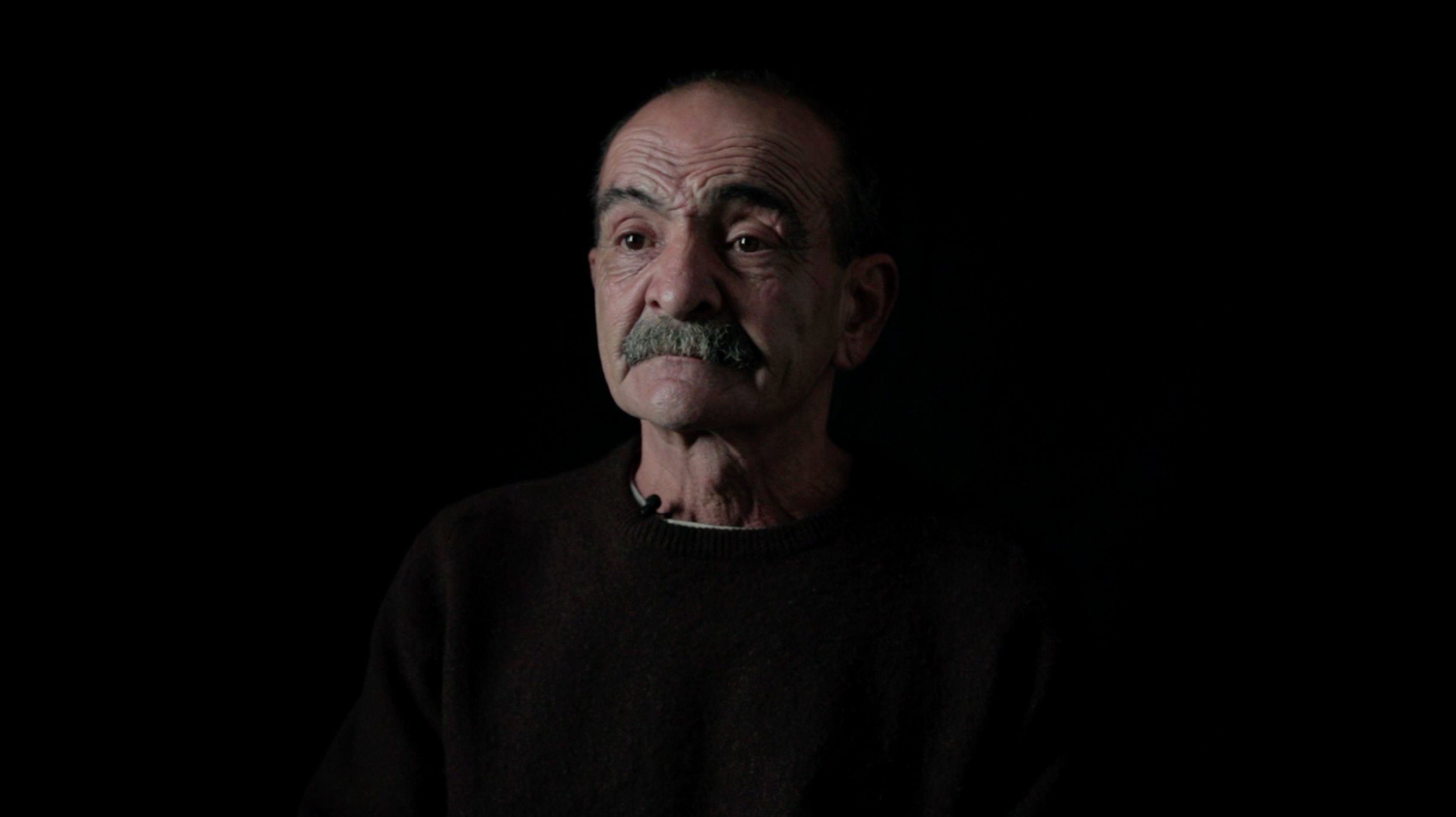

Salomé Lamas, Extraction The Raft of the Medusa, 2019-2020, still. Courtesy of the artist and producers.

SM: You're essentially referring to projects such as No Man's Land (2012–2015), Eldorado XXI (2015–2016), Fatamorgana (2016–2019), Extinction (2015–2018), but also Extraction: The Raft of the Medusa (2019–2020), or even Hotel Royal (2020–2021). Your work has a strong political dimension. How do you see your role in a world in crisis?

SL: I'm referring to those projects, but also to Gaia (2020–2022), Ouro e Cinza (2022–2025), and to what concerns me now. This journey, along with my pedagogical activities, has exposed me to a range of human territories as well as diverse production contingencies. Like everyone else, I make private and social choices, and I want them to be conscious and informed.

We can ask ourselves whether there is a need to produce work politically, instead of producing political work. What is the difference between the two? Is it possible to produce work without political ramifications? The answer lies in how one interprets the political. There is a distinction between producing politically and working with overt political themes or content. Now, we know that power relations operate within the intimate realm of our lives, and they can be analysed from various angles. For example, we can observe how technology and the tools that define our activities are never neutral, as they are always contaminated by ideology. To work politically is to question my position. It would be contradictory to address a political theme while reproducing the language of the dominant ideology and its mechanisms of oppression. When you work politically, you have to politicise every aspect of production. What I want to stress is that there are no apolitical works—only works that politicise the daily realities of our lives, and others that merely observe them, without offering the spectator a critical space where the tensions between the political and the personal can unfold. When someone says, “I'm apolitical,” it simply means, “I haven't politicised my life or my work yet.”

I believe that these two dimensions are recognisable, although not always easily so, given prevailing ecologies of production. We want the work to reach people because we are interested in showing it, in opening connections, stimulating discussion and change. I believe it's more effective if I don't tell you what to think. People don't want to be told what to think; they want to make their own decisions. On the other hand, the themes and contexts I work with are far too complex, and it would be irresponsible of me to present a single perspective. The problem exacerbated by the lack of transparent referents is that people want to stop thinking and deciding for themselves.

It's complicated because what drives me is a mix of scepticism and idealism. I would say that I see nothing but suffering in the near future of humanity. I feel that, on so many levels, we are at a point where it would be extremely difficult to repair the wounds of capitalism as a global system, compounded by a series of other factors such as individual and political exhaustion, economic collapse, environmental degradation, mental health care, and the fact that education and human rights have gone back to square one all over the world.

When you put all these factors together with the acceleration of time, the rhetoric of progress, widespread misinformation, the erosion of transparency, privatisation, and the unaccountability of the remaining democracies, which leads to modern ways of servitude and to increasing concentrations of power, you get an unattractive picture of the world to come. And I don't think we're at the worst of it yet. It would be imprudent not to mention here the rapid development of artificial intelligence, which is revealing itself both as a contemporary political project (Silicon Valley technofascism) and as a total social phenomenon—one of communication, power, and human transformation.

Now this would take us to an entirely different conversation. There is no “must” in history, and the present is as much a riddle as anything that lies ahead. We may be facing a temporary aberration, a new stage of development, or just the default setting of human society.

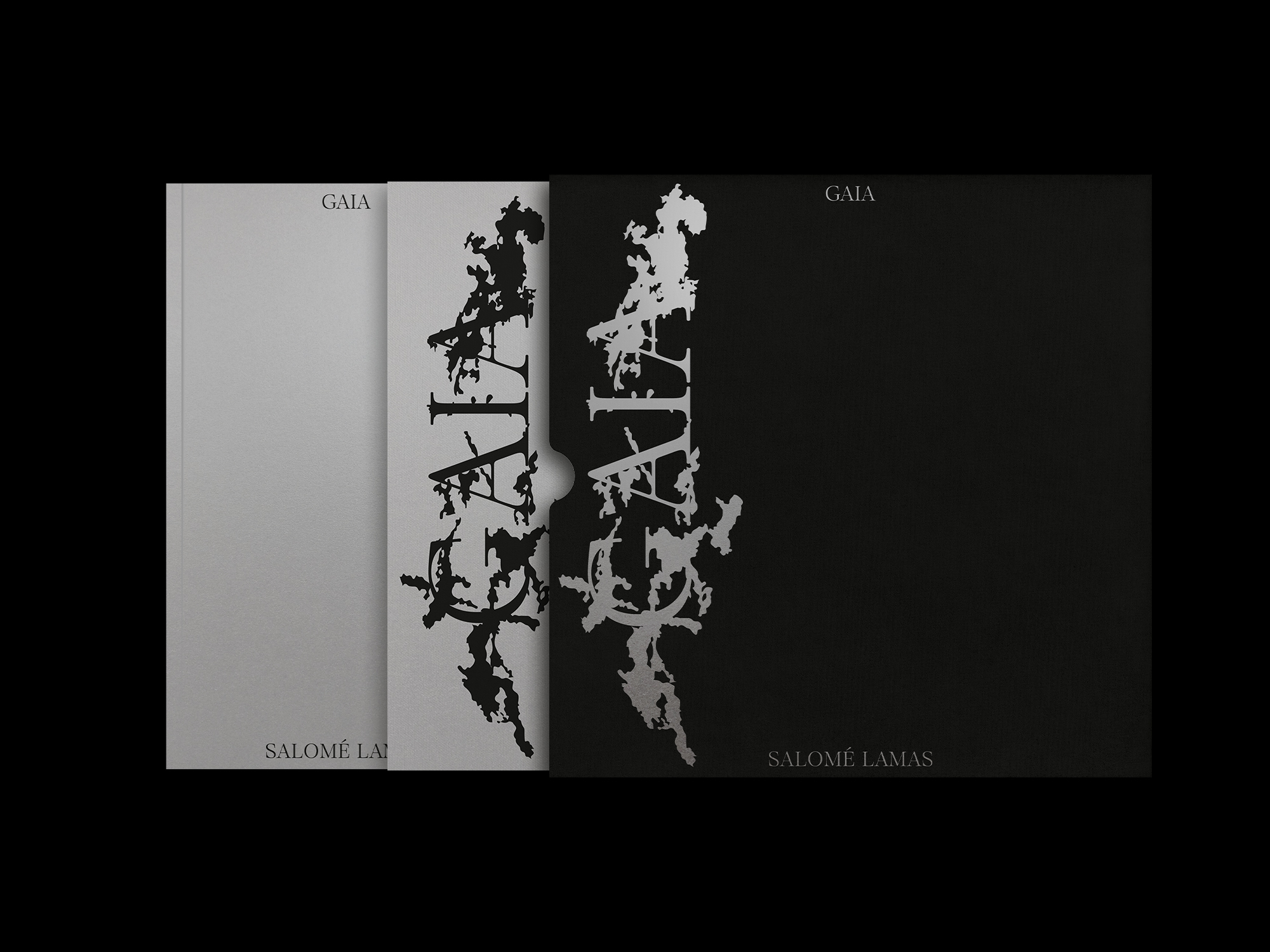

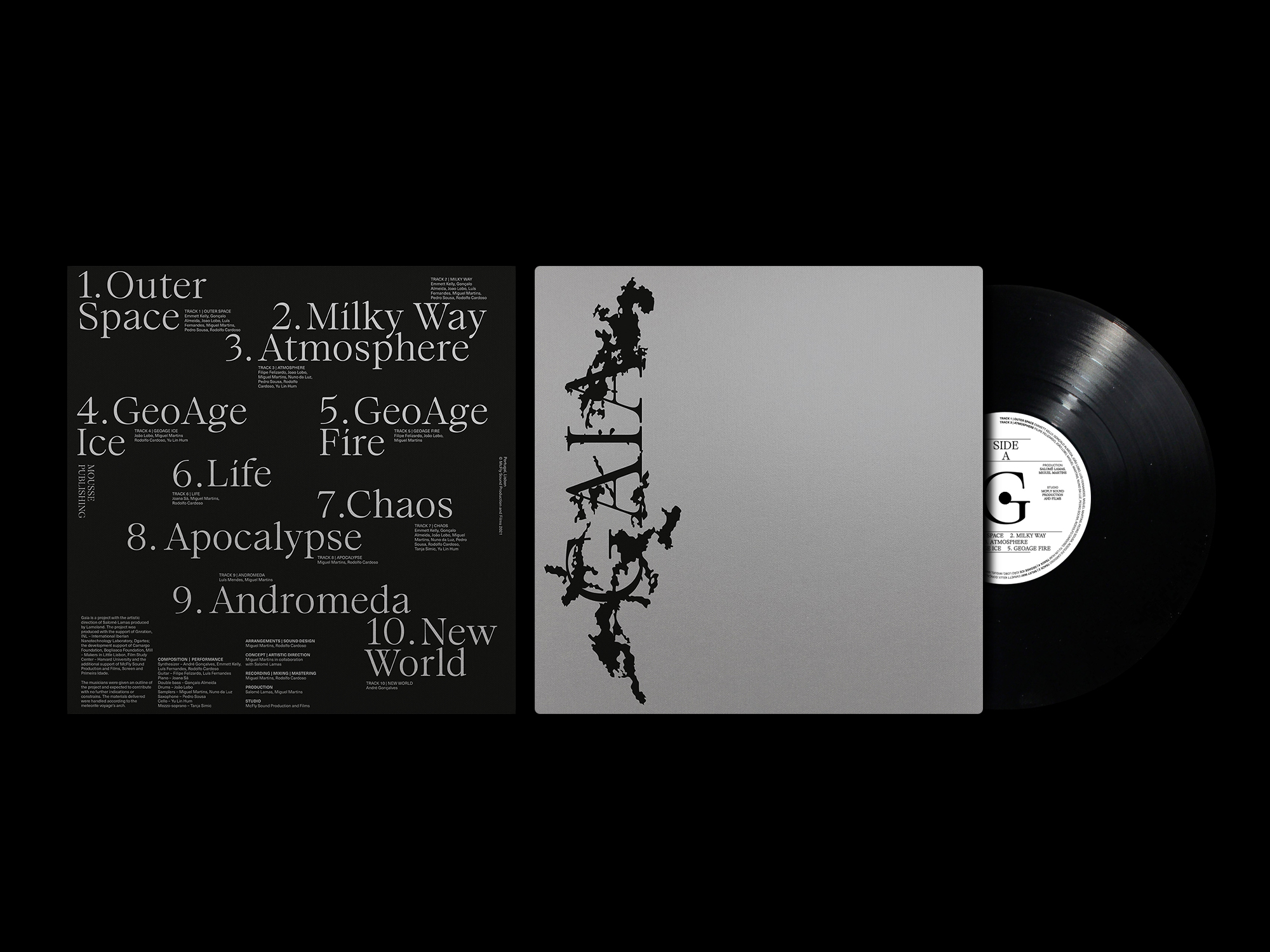

If we observe the previous projects, these are symptomatic of a political involvement and of a desire for subjection to the world. Contrary to the prevailing discourse, let us reject the individualisation of social problems. No Man's Land (Berlinale, 2012–2015) is a film about a perpetrator: a commando in the Portuguese Colonial War, a mercenary in El Salvador, and, in his own words, a hitman for the Spanish GAL. El Dorado XXI (Berlinale, 2015–2016) was filmed at an altitude of 5,500 metres in a Peruvian community whose primary occupation is gold extraction under the unjust system of the cachorreo. Extinction (CPH: Dox, 2015–2018) was filmed in Transnistria, where the main character had to obtain a Russian passport to travel to Europe. The team was also interrogated by the KGB near the Ukrainian border in 2015, during the period when Crimea was being integrated into Russia. Fatamorgana (Culturgest, Mousse Publishing, 2016–2019) is a video installation that explores identity and geopolitics in the Middle East. Extraction: The Raft of the Medusa (presented at Interdependence, Rome, 2019–2020), with the partnership of the United Nations, is a global project on migration and climate change. Hotel Royal (Locarno, 2020–2021) is an incomplete mosaic of contemporary Western societies. Gaia (Mousse Publishing, 2020–2022) was developed in partnership with an international nanotechnology laboratory and focuses on the journey of a meteorite. Gold and Ashes (DocLisboa, Mousse Publishing 2022–2025) explores the relationship of a mother and daughter, and in parallel the relationship between humanity and planet Earth. So far, I've worked in a wide range of diverse contexts and geographies—not only to produce and present work, but also through educational activities—which has given me a broad perspective.12 13

Salomé Lamas, El Dorado XXI, 2015-2016, still. Courtesy of the artist and producers.

These works—whether featuring modified ethnography, performative elements, or allegorical qualities—explore the traumatically repressed, the seemingly unrepresentable, and the historically invisible, from the horrors of colonial violence to the landscapes of global capital. They operate at the intersection of history, myth, and the liminal spaces of human experience.

In this context, I recognise that I cannot avoid introducing the preconceptions inherent in favouring marginalised perspectives—whether repressed or ambiguous, literal or metaphorical—that challenge dominant ideologies. I am interested in deconstructing the dynamics of power and control, and in observing ways of surviving along geographical, ideological, and existential borders. In essence, the work examines the invisible systems that govern our lives and the spaces where self-determination and subversion can emerge.

Returning to the question of how work is produced and distributed: this has always been a site of tension. In material, political, and aesthetic terms, I tend to favour an economy of means, resulting in minimal, formalist, and constructivist frameworks, with an orthopaedic metric of the image that aims to attract attention. Ethically, however, the work is uncomfortable and reflexive; it reveals its own construction and requires the spectator to adopt a critical stance. If we reconsider the autonomy of the artist today and how the art ecosystem operates, the equation is far from harmonious. Creatively, it is a challenge to balance ambiguity and clarity—to create a narrative that invites questions without overdetermining the answers. Professionally, it involves securing the resources and autonomy necessary to realise projects that may not align with the priorities of cultural policies. It also demands the clarity and confidence to be selective about commissions, invitations, and funding, in order to preserve the spaciousness, intentionality, structure, and spirit of the work—especially in the face of pressures for constant production. On a holistic level, I confront the emotional and intellectual price of engaging with stories of violence and oppression, while striving to ensure the work retains a sense of humanity and contributes meaningfully to the current discourse. It requires a sustained commitment—an effort of resistance and revelation—a way of seeing that involves not only exposing absences but also exploring presences, inviting us to rethink what is visible, permissible, and knowable. In general, I am not interested in—and I find dangerous—the systems of recognition and the perpetuation of positions, but I believe that we can create cracks in the dominant thinking.

SM: Gold and Ashes (2022–2025), the project you recently finished, took several years. You were in Nigeria in 2022. What are your next projects and challenges?

SL: Projects of the scale of Gold and Ashes (2022–2025), which resulted in a feature film, an installation, and a record-cum-publication, take time and involve dynamics that don't depend exclusively on me. The larger the scale of the project, the greater the production value, the number of interlocutors, and the smaller my agency over its development and production ecosystem. This tension can become particularly painful when it becomes clear that what happens is not in the project's best interest. Once it is concluded, there is a sense of relief in knowing that it is no longer in my care—that it has finally separated itself from me.

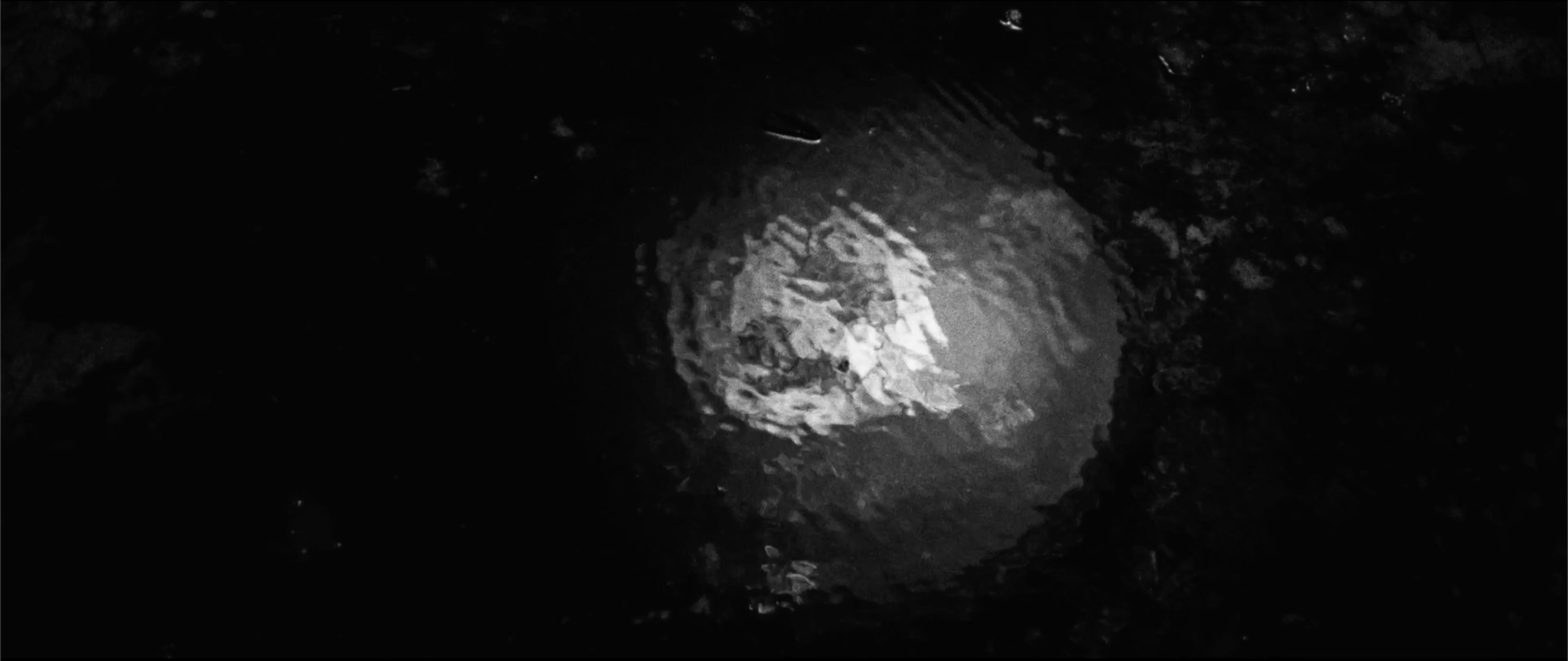

Let's talk again about our world in crisis. Our first object of inquiry and care should be life. We know the reason for that, as we are living beings in a situation in which the conditions of life are endangered. What is largely absent from this insistent ecological discourse is death. While the difficulty of acknowledging death is not new, in our contemporary situation death has taken on a new face. Gold and Ashes (2022–2025), as a theory-fiction, extends beyond representation to become an intimate act of excavation that proposes to mediate—materially, politically, and metaphysically—the reappropriation of death as power and our sovereignty as mortal beings in the private and social spheres, while speculating on the implications of representing trauma and the aesthetics of disappearance.

The project emerged from a moment of disorientation, as if I had suddenly ceased to understand the world.

It allowed me to explore new dimensions in the work. Articulating two planes—one concrete and one abstract—was challenging, because it sought to formalise dualities inherent to human beings and to our perception of reality.

Gold and Ashes adopted production models associated with fiction. Currently, I'm concerned with realising what I set out to do in the Niger Delta: a project that operates in the field of non-fiction (documentary). It aims to expose the complexity of the crisis that emerged in the region during the colonial period, characterised by the exploitation of natural resources by a consortium of multinational corporations. It also addresses the complexities of smuggling ideologies and clandestine economies in Nigeria, as well as the neoliberal risks associated with neocolonialism. I began researching the topic remotely in 2016, adopting a similar approach to Eldorado XXI, as both works explore extractive economies. However, it wasn't until I visited Nigeria in 2022 that the project took on a more defined shape. You can't witness the humanitarian and environmental crisis there and remain indifferent—to me, that would be wrong.

This doesn't mean that I haven't kept track of what I haven't done or found in previous projects, that I'm overwhelmed by other contexts that lead me to think about new projects, or that I'm not working on different, smaller projects at the moment. I realise that for personal reasons I feel the need to step outside my comfort zone and continue exploring new languages, which is why I accept invitations for plays, cross-disciplinary collaborations involving art, science, and technology, and commissions whose themes aren't obvious to me and lead me to interact with interlocutors that I wouldn't otherwise think of or encounter. This is also how I began showing work in the context of contemporary art, despite my background being primarily in film, with the visual arts coming later.

On the other hand, I always have multiple processes running simultaneously, as projects follow very uneven development and production timelines in terms of funding and scheduling. It's not uncommon for a project to give rise to several others, which is why they tend to overlap and contaminate each other. These are somewhat cumbersome, consuming processes, and it is often comforting to have other projects in progress.

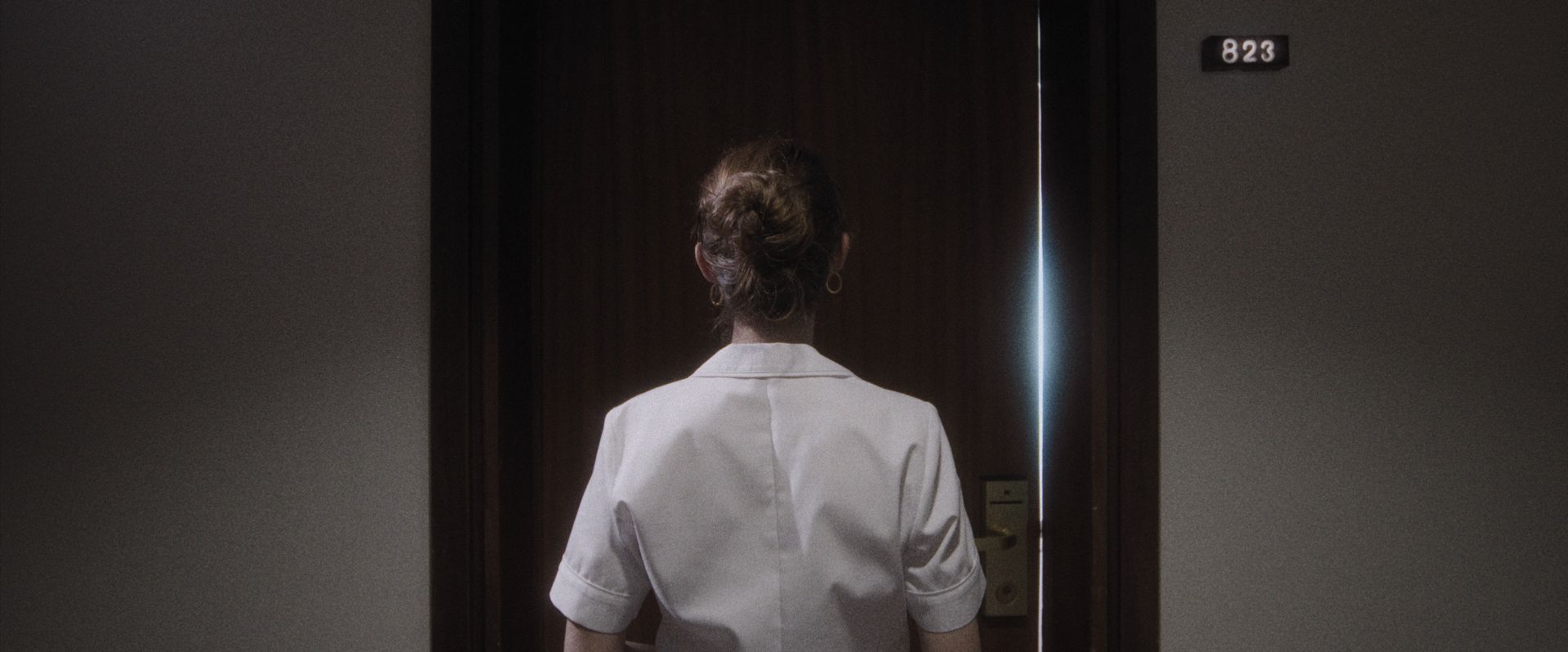

Salomé Lamas, Gold and Ashes, 2022-2025, still. Courtesy of the artist and producers.

SM: Is the way you work in the field of fiction and documentary different? What are these differences, and how do you navigate them?

SL: Yes and no. What I want to explain is that I recognise that my behaviour and being differ in the two fields, but in both it is impossible for me to completely disconnect production from directing. Let's think again about the binomial of fiction and non-fiction, which I believe is essential to preserve. I think it's dangerous to collapse this distinction, because it would completely alter what we perceive as reality. Similarly, I'm interested in keeping this distinction when it comes to the production mechanisms of these projects.

The writing and development process, in the classical sense, originates a document (a script or a cinematographic treatment) that provides the foundation for the entire production (pre-production, shooting, post-production). It is this document that enables communication, as it allows the team to envision the materialisation of our goals. Given the funding allocated to the project and the production model chosen, my experience so far is that the pre-production phase in fiction mainly comprises a survey of the script in terms of characters and the development of the action (casting), locations where the action takes place (sets), props and closet (art direction), atmosphere (cinematography), sonority (sound direction), among other aspects. Only after this survey can the shooting plan be established, which rarely follows the chronology of the film. Everything must be calculated so that the orchestra (team), comprising hierarchies and varying levels of freedom, sounds in harmony. This suggests that what has been planned is then (during shooting) consummated in a controlled manner. It's fascinating to watch what has been written take shape through a kind of collective psychosis and gain momentum through artificiality.

The problem is that not only are there no perfect productions, but dealing with the process of materialisation can be painful for countless reasons: difficulties in communicating needs to the team, dealing with their intervention, managing resources and schedules, mentally projecting infinite ramifications, or the eventual inability to formulate a satisfactory combination that aligns intentions and expectations with what the production makes available). If you like, I'm dealing with a straitjacket imposed on me. It is productive precisely because it is painful—because of the resistance and the possibilities it opens up. The same doesn't apply to the non-fiction (documentary) scenarios I work on. When operating in unstable terrain, where I'm rarely able to identify characters, locations, and establish a shooting map in pre-production, everything is wide open. Here I work with small teams precisely because I'm interested in breaking down hierarchies, but above all because they allow for greater agility. These are circumscribed realities to which I don't belong, and which don't know me. I use the team—a strange body—to trigger action, and I believe that it is in waiting that the extraordinary happens. Embodied waiting allows for a different perception of time and attention. Thought must be empty, waiting, not looking for anything, but ready to receive whatever might penetrate it. What interests me is ensuring the allocation of working time and resources (human and material) necessary to bring intentions to fruition. The referent of the materialisation is different.

In both operating modes, there is a team walking with me. Still, the profile of this team and the reasons for their participation tend to become more evident in non-fiction contexts—especially as these projects often test limits and may involve a degree of risk. In both cases, we are engaged in a kind of social experiment, where preparation and trust in the team are fundamental.

SM: There is a dichotomy in cinema between those who have the experience to tell and those who want to explore the experiences of others. How do you deal with this?

SL: I wonder whether the question doesn't refer back to its referent. What would happen if we didn’t treat this as a dichotomy, but instead saw it more as a continuum—or even as an interdependent transaction?

This dichotomy is not just theoretical. I carry experiences—geographies, voices, inheritances—that insist on inhabiting me. Encounters that shape my perception and demand articulation. They are not mine by possession, but by the way they affect me. Where does my experience end, and where do I translate the experience of the other? How do I balance fidelity and freedom in this transportation of languages? How do I establish the distance and conditions of this transaction?

This is where the work is shaped by an ethics—one formed in response to multiple, coexisting, paradoxical, and decentralised subjectivities. I don’t avoid the dichotomy; I seek to reveal its contours and thus define a methodological approach, an ethic, and a way of working. Ultimately, we are speaking of power dynamics—and how to make that power productive. Power circulates, and in that circulation, it organises social relations, governs conduct, and shapes what can be thought, said, and done. This leads us to the intentions and ethics behind the work—what is produced, for whom, and under what conditions. If power produces subjectivities, how can we intervene in those processes of subjectivation? How can we (re)configure power relations so that they do not only normalise, discipline, or exclude but also open up new ways of being and behaving?

In concrete terms, I can emphasise my position and outline the processes of extraction, with all their limitations and shortcomings. The reflexive act—and my position—becomes part of the work’s signification. I can establish collaborative structures to create a space of exchange, where authorship is indistinct. I can choose not to represent. I can, to the best of my capacity, divest myself of predetermined content to receive the other in a particular way. I can suggest absence (silence), ambiguity, and fragmentation. I can question my construction—and what it means to claim authenticity. I can speak nearby, which is different from speaking about. I can establish a space of affective resonance rather than discursive clarity, opening an ethical and aesthetic terrain that does not evade appropriation but invites encounter.

My positioning, above all, is critical; it provokes discomfort. In the search for counter-discourses, resistance is not negation but invention. It speculates spaces where new forms of organisation can emerge. After all, ethics is about being equal to what happens to us.14

Salomé Lamas, Terra de Ninguém, 2012-2015, still. Courtesy of the artist and producers.

SM: Following up on the previous question, how do ethical considerations inform your work?

Highlighting the ethical plane over the aesthetic one in any creative activity can be dangerous and misleading. The artist is a constructor, and it is in this act of construction that the ethical plane resides.

I stand before a world in motion—a succession of events—and I try, with tools (or without them), to relate to it. In this process, the work transcends mere testimony to become an active gesture that prolongs and deepens this engagement. It not only represents but also establishes connections, poses questions, transforms the represented, and challenges its authority. 15

Ethics is not a moral guarantee of legitimacy, but a dimension I question and work through during the process. It is a transaction—with those I work with (a relationship), with what I encounter, with the approach, with the apparatus assembled, with the formal decisions undertaken, and with the position from which (and for whom) I speak.

When working with reality and questioning the limits of its translation, it is essential to stress that bringing private matters into the public domain demands responsibility. One never emerges with clean hands. I believe that occupation—as an outsider—through presence and waiting, generates productive tensions.

I am responsible for those who work with me (team and cast, including non-actors),16 as well as for the spectator. This triangulation is central to my practice, though it remains entangled with broader economic, political, and social forces. Such an approach requires time, presence (attentive listening), and patience—particularly when working in remote, culturally distinct areas where realities resist description or representation. Now I ask directly: can someone from a colonising country contribute to postcolonialism in any way other than as an object of postcolonial studies? This question must be asked, given a certain nativist essentialism that sometimes infiltrates postcolonialism. If it is difficult to answer the question Can the victim speak?, it is even more difficult to answer Who can speak on behalf of the victim? In today’s polarised world, many simplistic discourses lay claim to diversity and decentralisation, which I find dangerous. Often, these discourses reproduce the very systems that have structured and normalised violence in society, perpetuating dynamics of exploitation and domination. Perhaps this is a passing necessity in the search for a more balanced world. I refer here particularly to political and social structures. Even so, nonviolence is not simply the absence of violence. It is an active refusal to participate in the violence of exceptionalism, exploitation, and marginalisation, in favour of a commitment to interdependence.

I’m interested in the double movement between concepts and metaphors. A concept is a way to encompass a certain reality, a way of dealing with the real, whereas a metaphor is the exact opposite. A concept always aims to produce an order, the order of things, while a metaphor is a transgression. It's not a substitution but rather what happens when two heterogeneous realities encounter each other. It's important to remember the metaphorical origin of concepts—a way of adding a new signifier or ratifying a signifier—to enable new translations and rectifications. When a concept becomes too fixed and we forget its transgressive origin, it becomes a dead tool that can no longer function. It is misleading to erase the difference between concepts and metaphors. To complete the unfinished hypotheses (revolutions) of the past, what is needed is an encounter with what happened and what failed to happen fully. This encounter produces the desire to complete something. But to complete what remains unfinished, we need new parameters: new modes of expression and new strategies. Democratic processes are unfinished—we know this. And the difference between centrality and position lies in understanding who the subject of the revolution will be. A political revolution must prevent society from absurd or forced becomings. We must recognise that at the core of the human, there is something inhuman. This inhuman part should not be suppressed; it resists all forms of education and normativity, and, precisely for that reason, it can serve as a revolutionary force. 17

I am aware of the power and violence I can exert—even unintentionally—but in violating the other, I would also be violating myself. The work is where these tensions become visible. This disquiet interests me—it neither relieves nor crystallises, it doesn’t prevent faults but instead assumes confrontation and complexity. The work should not be a form of domination over the world (nothing should be), but a way of sharing its density and of constantly questioning my position. It’s about making power productive—for the common good.

SM: Some of the realities you've worked in are harsh, as in the case of No Man's Land (2012), Eldorado XXI (2016), Extinction (2018), or the new project you mentioned. I imagine that creates a significant emotional impact. How do you deal with it when you return home after spending so much time immersed in that reality?

SL: I feel that, upon returning, there’s a disconnection between what I’ve lived through and what others can understand or perceive. When working in certain extremes, I instinctively create a kind of armour. When I come back, it softens—and I get sick. This can also apply to more controlled contexts in the field of fiction, but it stems from different factors. It’s not easy to explain what one feels when people’s lives depend on decisions that seem entirely out of their control. The way this affects my perception of the world brings me great discomfort. It’s something I continue to work through. The projects offer themselves to the spectator and provide means for other fields of study and production. Sometimes I ask myself whether, by coming into contact with violence and cruelty—by exposing myself to those spaces of “nowhereness” where angels and demons coexist—I’m not somehow contributing to their perpetuation. I wonder whether, in the process, I’m not becoming a worse person. And when I feel the need for relief, I try to seek out things that connect me to calmer, more balanced space—or simply to conversations with people who share broader perspectives.

SM: Does cultural policy also influence that?

SL: Yes, I was clear at the beginning of our conversation about artistic autonomy, particularly given the role cultural policies play in defining the conditions of production and distribution. Cultural policies determine access to production resources (materials and economic), and tend to prioritise themes such as identity (individual and national), diversity, or innovation. While they occasionally allow space for critical work, they also invariably instrumentalise it. These policies regulate not only access and visibility through channels of legitimation, but also content, aesthetics, and markets. The equation is inverted. And it is becoming increasingly complex to secure the fundamentals of art through disinterested stewardship in the face of self-exploitation in the performance society.

We have emphasised meta-narratives that connected art and knowledge to progress and emancipation, while also stressing the need for constant questioning of the existing systems, arguing that art enables the critique of societal norms indirectly through aesthetic experience rather than through overt political engagement.

Yet we are constantly reminded that art is deeply embedded in power relations. It is conditioned by historical and social forces that are often institutionalised by the market and shaped by systemic inequalities. This raises a fundamental question: should we then emphasise art's political engagement and its entanglement with cultural and social contexts that reject totalising systems in favour of deconstruction and a sensitivity to difference?

But attributing to art a status of exception—not independent from political systems, but rather relative to ordinary social relations, enabling it to (re)imagine societal norms, ensuring cultural democratisation by promoting equal access to cultural production and expression, and exploring how political frameworks can facilitate artistic freedom by addressing broader limitation, such as economic or social limitations—can in itself be problematic. Likewise, emphasising the interconnectedness between artistic practices and their sociotechnical environments, where technological mediation is not a backdrop but an active component that preserves art’s potential for critical agency and democratic participation, becomes problematic over time.

What I want to underscore is that cultural policies18 are a reflection of the world we live in—and that’s precisely where things become blurred. Currently, as we strive to adopt more conscientious practices (if discernment still holds any value), we are increasingly witnessing the expansion of creativity as a marketable form of labour. Creativity—facilitated by social media and audience-building platforms—has become a generalised cultural value that blurs the boundaries between art, consumption, and self-promotion. Much of today’s production—fast, spectacular, and disposable—is driven by this logic of profitability. That is why autonomy, if it still matters, should not be understood as an escape from politics or ideological hegemonies, but rather as a site of resistance—one that reveals, rather than conceals, the tensions between art, labour, and capital.

SM: Is teaching part of your practice?

SL: I started teaching to pay for part of my education,19 and today I teach out of vocation. I’m thinking about your question in a broader sense, and I believe it’s important to contextualise the diversity of experiences I’ve had so far, a bit all over. Currently, I hold a temporary position at a public university in Portugal, and I have previously taught or conducted visits at other national and international institutions. I’ve always enjoyed learning, and school was part of that path. I was convinced that knowledge would bring me closer to the adult world. At the same time, school offered a form of structure that contrasted with a less structured domestic environment. Perhaps because I was exposed to other kinds of content and interests at home, I began seeking materials beyond textbooks and what was formally taught in class.

My engagement with both formal and non-formal education systems is essential to my practice, even as I continue to explore alternative pedagogies20 and confront the conservatism and resource limitations that persist in many educational institutions. Once again, I advocate against the inversion of the equation.

One fundamental aspect to address is the tendency of education to shape, normalise, and control individuals in the service of sustaining existing power structures—through disciplinary systems and the reproduction of cultural capital. Another aspect is that educators who teach through practice and think through ideas in the process of making work are often better equipped to teach younger generations—especially when it comes to practical subjects—unlike the widespread tendency. We cannot theorise about art, but only with art. This is how the fields of film and the visual arts can remain open.

Our public education system remains, to a large extent, grounded in pre-established models that prioritise IQ, particularly memorisation and standardisation. There is a need to reform education to meet current demands and, more specifically, the needs of today’s students. The pleasure of learning is indispensable; without it, there are no students. In learning, there exists a particular kind of waiting—a disposition in which we give our attention to a specific problem without immediately seeking a solution or demanding signification. We simply wait. This form of attentiveness is fundamental. Students should not be treated as clients receiving a service; rather, we must care for the new generations. We should be moving from matters of fact to matters of concern, promoting indiscipline, creativity, and critical engagement. This is especially complicated at a time when the civil body politic is in decline and we appear to be entering a form of neofeudalism. Moreover, access to education—as well as equity and quality—still requires substantial improvement.

Approaches to knowledge in education can benefit from a networked sensibility that foregrounds the negotiated processes through which material becomes entangled with the social, giving rise to actions, subjectivities, and ideas. Socio-material approaches to education share analytical perspectives in the sense that they refuse to separate human dimensions and educational practices from their material dimensions, focusing instead on the relational composition of these practices. These approaches provide a criticality that opens up necessary entry points for rethinking learning processes and educational institutions.

Previously, the creative visual arts were seen as contributors to knowledge, but not as problem-solvers—and, therefore, not to be taken too seriously. However, the idea that the arts can be more than creative production—that they can constitute intellectual enquiry and contribute to new forms of comprehension and perception—is a step that questions what is valued as knowledge. At a time when knowledge is acquired at dizzying speed—impacting not only content production but also its distribution to growing audiences—it becomes essential to establish models for evaluating and legislating that mitigate damaging effects. In this context, both the practical and theoretical domains hold simultaneous interest. They intersect within participatory environments where hierarchies can be questioned, where laboratory-style exploration fosters students’ autonomy by prioritising learning processes and individualised interests, and where community forums promote collective debate. Multi- or (inter)disciplinary approaches hold the potential to uncover new modes of objectivity and to offer tools for bridging current methodological divisions. This derives not only from the complexity of contemporary problems, but also from the limitations of existing research models in addressing them. Knowledge practices are specific material commitments that actively participate in the (re)configuration of the world.

There is work in which I attempt to think through materiality. Thought paves the way for materiality, but the reverse also applies. We can start from the condition that art produces sensations and compositions, while philosophy produces concepts.21 Yet, it is interesting to explore their processual relationship—where artistic materialisation can facilitate the consumption and embodiment of the concepts it generates. As though the invisible could be made material. It's important to note the agency of this process and the initial foundations that inform it. Once again, I return to the need for a structural framework—a path—and the identification of fundamental questions (so they may be preserved). This model enables us to validate developments and to move forward systematically. It is easy to perceive the element of risk that is explored, since these paths are hypotheses—not always satisfactory ones. Each project is unique, and therefore, the models are unrepeatable. Materiality does not concern only tangible material questions or percepts. On the contrary, it seeks to make the invisible visible and the speakable unspeakable. In doing so, it not only confronts its own limits but must also engage with all the factors discussed throughout this conversation—factors that cannot be treated as mere accessories to the production process. And yet, even if we try to detach from these conditions, we encounter the limits of construction: observe the ways materiality is subjugated to demonstration, or how it may ultimately fail to reach full consummation.

No long-term political commitments can be sustained without the right education. By education, I mean the transmission of knowledge to the next generation—and to generations beyond. To foster that kind of engagement, compelling narratives about the world and about human beings are needed—not in the classic Enlightenment sense, but in ways that genuinely inspire people to take responsibility.22 Grand narratives, by definition, need not be incomprehensible or fragmenting. They can be totally different from what we have now.

Salomé Lamas, Extinction, 2015-2018, still. Courtesy of the artist and producers.

Salomé Lamas, Hotel Royal, 2020-2021, still. Courtesy of the artist and producers.

Salomé Lamas, Gaia, 2020-2022. Courtesy of the artist and producers.

The work is available at: salomelamas.info

- One could argue that a finished work is a failure because it was fixed at a particular moment in its development, and because its potential for evolution has been amputated. There are two forms of agony here: that of the finished work, and that of the lost work—the unbearable pain of the incomplete.

- Walking is neither a means nor an end, but a process-in-becoming—a phenomenological, participatory, and open practice that values experience over goals or results. Its physical mobility and fragmentary perception are conditioned by both objective and subjective geographies, emotional states, and meteorological events.

- These cross-cutting issues have contextual and local implications. Basically, they are the same aspects that drove me to found AAVP (Association of Artists in Portugal) in 2020. And they are what I try to convey in formal and non-formal educational contexts, nationally and internationally.

- Referring Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari.

- Particularly visible in multiform projects such as Fatamorgana (2016–2019).

- When we conceived the documentary exhibition Salomé Lamas Paraficção at Batalha Centro de Cinema, Porto (10 December 2023 – 3 March 2024), to which you contributed a text.

- Perhaps it's important to explain that what I related to in 2012, when I came in contact with Carrie Lambert-Beatty's article “Make Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility” (2009), then took on independent derivations. Basically, I appropriated the concept to explore the authority of representation in No Man's Land (2012) but also to frame the diversity of languages and formats that the work was beginning to reveal.From that moment on, I began a theoretical and practical research project, Problems of translation and critique in Parafiction, along with educational activities, which have manifested themselves not only in my practice but also in exhibitions, retrospective series, publications, and institutional invitations to speak on the subject.

- In Walter Benjamin.

- I'm thinking of Roland Barthes and Jacques Rancière.

- Honoré de Balzac spoke of being the secretary of history in his social chronicles, as noted by Alexander Kluger in the fragments of Chronicle of Emotions.

- As understood by Simone Weil in Waiting on God, study is not just an intellectual effort, but a form of attention—an exercise that does not include production.

- Some formative paths didn't trigger projects. In Borneo, in 2016, I came into contact with the Dayak tribes who are divided between serving palm oil multinationals and resisting to protect the forest. I was invited to visit the Amazon in 2018 to document the kuarup of the Kamayurá people, and territorial conflicts of the Mapuche in Patagonia in 2019.

- We're talking about geographies as diverse as France, Spain, Germany, England, Italy, Belgium, Denmark, Georgia, Czech Republic, Austria, Sweden, Switzerland, Moldova, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Lithuania, Norway, The Netherlands, United States, Canada, Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Peru, Mexico, Brazil, Nigeria, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Egypt, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Hong Kong, among others.

- As Gilles Deleuze said in Spinoza et Le Problème d'Expression.

- Etty Hillesum records what passes through her with extraordinary intensity. She is neither a distant observer nor an authoritative narrator; she is not there to judge but to perceive, retain, and bear witness. Aware that love for all things is more beautiful than individualised love, she opens up a radical ethics: one of being present with lucidity and generosity, even when everything invites flight or collapse.

Hannah Arendt, by contrast, contemplated these matters without having experienced internment in a camp, and she focuses extensively on judgment and the capacity to judge from a position of distance and shared responsibility. - I'm talking about territories without diplomatic representation, territories controlled by systems of political violence, the personal safety of those involved, of communications and the material collected, physical constraints, and the salubrity of food for consumption. I'm talking about realities where a shooting map is of little use, and for this reason, you have to manage the expectations and work cycles of the team in extraordinary ways.

- In conversation with Frédéric Neyrat in 2022.

- Which I benefit from as a filmmaker/artist but also as a spectator, and with which I collaborate when I accept institutional invitations or funding, for example.

- While I was an MFA student in Amsterdam, I started giving workshops in disadvantaged contexts for young people with UNICEF. The last one was in 2013 in Zimbabwe because I didn't feel comfortable in the position I was in.

- Isabel Lamas received students and supported families that today we classify under special schemes. She was an educator and writer of textbooks, children's books and songs.

- Referring to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari.

- In conversation with Reza Negarestani in 2023.